By Roger Nelson and May Adadol Ingawanij

Please note that this publication is currently under review and will be subject to changes.

Roger Nelson (RN): ‘It is just one sound among so many that are more audible, clearer and louder, and we hardly ever mentioned them before.’1 These are the final words in Araya’s text, commissioned for this publication on Womanifesto, and translated by Kong. I’m interested in considering the before. In an essay I co-wrote with Yvonne for another recent publication on Womanifesto, I mentioned that ‘I have been troubled by the tendency of Womanifesto to seem to lay claim to being the “first.”’2 My point there (a simple and uninteresting one) was that there is always something before the ‘first’ and that one contribution of feminist-situated knowledge has been drawing this to our attention, making this something we can learn from.

The before that Araya refers to in the above-mentioned sentence is the period of almost three decades since Womanifesto’s establishment in the mid-1990s, during which they have been almost entirely ignored by most institutions and discourses in Thailand, as well as in Southeast Asia, and beyond. People have ‘hardly ever mentioned them before’, as Araya puts it. All that changed a few years ago, with a series of symposia, then archives, then exhibitions, and now publications. After a long before of being overlooked, Womanifesto is now being celebrated.

I’m drawn to these final words in Araya’s text, and the couple of sentences that precede them, because their humility (whether it is sincere, or not) serves in part to undermine the message and tone (insofar as these are stable or clear, which they are not entirely) that Araya has established in the preceding pages of writing. Those final words, again:

But do not forget that this belittling statement is easier to make by someone who keeps a distance and does not partake in the difficulties and problematic structures that underlie a formation and sustainability of the art project.

So … just pay it no importance. Because there, did you hear it? The toob sound that closes off this train of thought.

It is just one sound among so many that are more audible, clearer and louder, and we hardly ever mentioned them before.3

In other words, Araya is quietly saying, ‘ignore me’, after several pages of saying other rather less humble and more strident things.

This move of Araya’s—this closing act of self-effacement—is at once generous to Womanifesto (perhaps surprisingly so), and also ungenerous to basic feminist principles of taking women’s lived experiences seriously, even those of women like Araya, if such a thing is even imaginable. Araya tells us not to pay attention to ‘this belittling statement’ and in the process belittles her own statement, even belittling its ability to be belittling.

I wonder if this might be a reflection of a (perhaps consciously or perhaps accidentally) shared circumstance: while Araya marks out her differences from the Womanifesto ways of thinking and being, here in these almost tender and vulnerable closing words, she is also suggesting that despite her differences, she might have shared a similar experience of the before: that is, of being largely ignored by most institutions and discourses of art, especially in Thailand.

Or am I being too generous to her in the context of this rather ungenerous text? It seems ungenerous in its spirit and attitude toward Womanifesto, I mean; it is hugely generous in its felicity to engender readings. What do you think?

May Adadol Ingawanij (MAI): As you say, the text comes across as a rather ungenerous response to a (wo)manifesto. I’m still not sure I would describe it as a generous addressing of its readers. But I recognise this feeling of disorientation it’s left me with. I’ve been here before when I’ve previously encountered Araya’s work. It’s like being pulled across a threshold while I’m standing there still deciding whether I want to enter. Now that I’m here I might as well do some thinking. What it is that’s making me disoriented, and maybe even a little bit cross? Is this unsettling text just reactive aunty stuff or is it provocation-as-pedagogy? Toob is an onomatopoeia signalling a clumsy monotonal drop. Yet its cousin is the snack toob-tab, made from pounding a gloop of caramelised peanuts into a thin silken strip. It’s very nice! Oei is intimately belittling, but with huge scope for queering. I wouldn’t ooeeeeeeeeeei someone if I didn’t feel I was in the same boat as them.

You are rightly troubled by the claim to firstness of Womanifesto. I wonder whether this is a criticism directed at a group’s decision to claim its legacy in this or that way, or whether you are identifying a problem of a more structural kind regarding the present-day mode of validating Southeast Asian contemporary art. Are we now in the moment of institutionalising the language and the framework for legitimising historically overlooked artistic practices, which at the same time normalises a blurring between publicity, exhibition discourse, and art historiographic framing? Your call for a more complex attentiveness to the conjuncture of the before makes me wonder what questions and methods would be needed to move us towards Southeast Asian art historiographic complexity, and towards Southeast Asian feminist art historiographic justice.

As part of the same generation of women practising art in a male-dominated artworld in late-twentieth-century Thailand, Womanifesto and Araya may have shared that experiential condition of being belittled and rendered illegible. And that might have been the extent of their commonality. How each claimed artistic agency and autonomy within a social and institutional conjuncture, and whether their respective modes of gestating artistic becoming within a particular conjuncture were tilting towards common or uncommon worlds, are questions worth asking.

RN: You make a good point about Araya and Womanifesto being from the same generation of women working in a male-dominated artworld in Thailand. In Araya’s 2005 book, (Phom) Pen Silapin, published in English translation in 2022 as I Am An Artist (He Said), she mentions Womanifesto only once. It’s a passing reference, but its context is interesting: it appears within a meandering musing about how ‘Thai female artmakers … still have to live with … limitations’ whereas ‘limitations … no longer exist today for farang women.’4 This rather dubious statement—surely an example of what you call provocation-as-pedagogy—comes soon after she cites the feminist art historian Whitney Chadwick, and artists like Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt that Chadwick and her peers had been (re)discovering and championing. These references make clear that Araya is well-versed in feminist art histories of the kind published by university presses in the West. A few pages earlier, she also cites another more regional and anecdotal source of insight. I think it’s worth quoting here:

I remember an angry Filipina artist who stood up on stage at a panel of Asia-Pacific artists in Brisbane spewing diatribes about domestic chores to the cheers of the audience. One night much later, I bumped into one of her friends in New York. After exchanging pleasantries, the friend said that the artist was ‘raising her child at home’. Now this artist is the curator of the Who Owns Women’s Bodies? exhibition; she has stood up strong again.5

Clearly, Araya has always had moods, and performed them in her writing. Perhaps she wrote her more recent text about Womanifesto in a less generous mood, and perhaps she shared this earlier anecdote from the Asia Pacific Triennial in a more generous frame of mind.

The point I want to make by mentioning these various citations of feminisms in Araya’s book is that she was clearly circulating in multiple, transnational artworlds. She studied and exhibited in Germany, of course, but was also a frequent appearance in the proliferating biennale circuits of the 1990s, showing at APT in Brisbane, at the Sydney Biennale, at Okwui Enwezor’s Johannesburg Biennale, and many others besides.

This sets her apart from most of the Womanifesto artists. While Araya was from the same generation as them, and shared a similar experience of male-dominated Thai artworlds as they did, she had a fairly frequent escape route whenever an invitation for an international showing arrived.

Womanifesto has always been remarkably international as well, of course, inviting artists from an astonishing number of countries to contribute to and participate in their projects, and thereby facilitating the kinds of exchanges that led to lasting friendships and collaborations, some of which continue today. The difference is that Womanifesto has mostly worked with international artists within Thailand, or at least on projects initiated in Thailand, whereas Araya’s practice has seen her making and exhibiting work in much more far-flung locations.

I don’t want to make a value judgement about either one of these approaches or circumstances being somehow ‘better’ than the other, but I do think the difference may be worth highlighting, if only because it reminds us that there has always been more than one artworld, and there have always been many feminisms.

MAI: Many years ago I found myself at a dinner in Oberhausen where Araya was present. As the night wore on, she and a dear friend of mine struck up a fascinating conversation. At one point he used the phrase ‘a type of artist’ to describe a mutual acquaintance. She immediately asked if it was possible to be an artist and a type. Artists are not fungible. Art is not functional, not standardised, not substitutional. Freedom of artistic practice means claiming the agency to create indeterminate forms from life as lived and feelings as felt, to make and to live with the unknown and the uncertain. That scene stayed with me, and I initially took it to be an expression of Araya’s commitment to a universal-claiming kind of modern artistic autonomy. What her recently translated book I Am An Artist (He Said)—an important initiative which you were involved in—invites me to do is to think more carefully, and with more sensitivity to both the potential and the contradiction of her practice of artistic autonomy in its historical context.

Araya’s book is many things, including a hilarious and affectionate caricature of the post–Cold War Thai contemporary artworld, itself connected with the national intelligentsia, and relatedly the patronage and cultural production networks that she and her artworld peers were all a part of. Poking fun every now and then at the critical and iconoclastic acting-out of her best-known, mostly male peers, I Am An Artist (He Said) is at the same time a fascinating portrait of Araya’s own incongruous enmeshment in that world of masculine artistic, intellectual and entrepreneurial vanguardism. In it, her practice was at times belittled for being seemingly too feminine, and at times vilified for its transgressions. Yet within that very same artworld she was the prize winning, internationally exhibiting, insider artist-ajarn figure. As the anomalous and sometimes marginalised, yet securely tenured artist in a society in which academia was, and remains, an auratic profession, we might say that Araya was the exception entwined in the dominant institutional infrastructure for artistic production in post–Cold War Thailand. In comparison, Womanifesto was an endeavour by precarious women artists to collectivise and to experiment with creating another kind of infrastructure for artistic production, one that might enable the production and sustaining of artistic practice for those excluded from the sexist, encaging yet production-sustaining institution of the auratic Thai university and the vanguardist establishment connected with it.

In this context, Araya’s response to Womanifesto feels to me like misidentifying a ghost. Art-for-life vanguardism in Thailand, aka silapa phuea chiwit, had emerged during the leftist revolts of the Cold War, a discourse valuing art on the basis of its responsibility as revolutionary, useful and socially developmental praxis. Later on, in the post–Cold War era, that vanguardism became a residual force endowed with critical, political, and market currency. The piece seems to me to conjure Womanifesto as a kind of village-women doppelganger of phuea chiwit. What to make of this?

The key question here, as I see it, concerns the genealogy of freedom within which artistic autonomy is situated. The task is to think through the overlap, difference, ambivalence, potential or aporia of claiming ying-ying artistic agency in terms of aesthetic autonomy, and in terms of the possibility of infrastructural change.

While you worry about Womanifesto’s retrospective claiming of pioneer status, I find myself worrying whether I am hallucinating another doppelganger scenario. Is there some kind of a genealogical relationship between the animalistic yet vitalist artistic autonomy claimed by Araya’s practice, and the ideology of vitalist freedom accompanying Thailand’s anti-communist modernisation, which was part and parcel of the United States’ Cold War propaganda pitting an imaginary of the Free World against Communist Totalitarianism? And what if, god forbid, this present moment enables us to perceive that Cold War ideology of freedom in Thailand as one of the precursors of the emergent far right ideology of ‘insurgent’ or ‘transgressive’ freedom in the current global conjuncture? Critical historiographies of Thailand during the Cold War era have done much necessary work contextualising artistic and cultural practices within the framework of Thai official nationalism, the formation of ethnonationalist Thai subjects, and Thai nationalism as royalist anti-communism.

There remains the need to study the formation and the conception of modern artistic autonomy within an ideological context that, up until relatively recently, has been associating unfreedom and brainwashing with communism, in opposition with and inferior to the virility, vitality and modern worldliness of the free world. In its time, Cold War propaganda produced a cultural imagination of communism as an incarceration; popular Thai fiction and films of this period regularly figured the communist as the robotic, brainwashed body. In comparison, sensuous expansiveness and cosmopolitan mobility was the property of the free world that had brought exhibitions of abstract expressionist art to cultural and diplomatic institutions in Bangkok, and movies to itinerant film circuits around the country.

RN: To be clear, it’s not so much that I am not critical of or worrying about Womanifesto’s claim to having been pioneers (even if growing up in a settler-colonial society did make me rather suspicious of and allergic to the very term ‘pioneer’). Rather, I’m interested in considering how the before might yield a fertile harvest of plural, sometimes even contradictory articulations and practices of feminisms in and for art.

Seeking that harvest—searching for those differences, even among feminists—is not always easy. Writing about Womanifesto in 1997, Somporn Rodboon chose instead to emphasise commonalities that artists participating in the exhibition shared:

Regardless of nationalities, cultural or language differences and beyond their shared characteristics, these women artists are bound together by the visual arts as their common language.6

As important as these ideas are, I also think collective and relatively non-hierarchical projects like Womanifesto also engender pleasingly and productively uncommon languages, revealing the things that unbind artists, individually and together. The drawings made during the LASUEMO workshops—and exhibited in the ‘Womanifesto: Flowing Connections’ exhibition at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre (BACC)—give a glimpse of this unravelled incoherence. One depicts an upright piano; its keyboard appears to be in a state of higgledy-piggledy ruination, and extra notes seem to be strewn at its base. Around this hastily sketched image are the words: ‘Also she changed an organ / big like a piano.’ On the other side of the same exhibition, one of Lena Eriksson’s drawings is accompanied by these words:

When Phaptawan tells about her work and her life, it seems to me as if everything is interwoven with everything else, a story without a closing point. Only, how am I supposed to tell this to my blind horse. Maybe I’ll just stroke his nose.

I feel drawn to these moments of confusion, unintelligibility, nonsense, opacity. While Somporn sees significance in artists being ‘bound together’ with a ‘common language’, I wonder if we might also find significance in moments of abstract poetry like these. Perhaps they suggest a possibility for a different kind of feminist refusal.

MAI: My hunch is to think more deeply about the significance both of Womanifesto and of Araya’s artistic practice. Taking both as exemplars of some kind of autonomous feminine/feminist/women-led practices, we would also need to think the potential and the contradiction of their practices in relation to the afterlives and the legacies of the leftist-vanguardist and the rightist-vitalist genealogies of autonomy in Thailand.

RN: Your invocation of the doppelganger(s) makes me really want to read that new Naomi Klein book that you’ve been talking to me about. (Imagine the conversations about books that must have taken place during Womanifesto gatherings … How different might they have been from the citations of books in Araya’s writing? What type of scholar would have made sense for a group of women relaxing on a farm?)

What type of scholar … Wait, can someone be a scholar and a type? Surely we say things like ‘this kind of book’ to our students all the time. Is Araya’s prickling at the suggestion that there could be a ‘type’ of artist just a reflexive retreat into the idea that artists are a special breed—even though this is an idea that Araya herself has critiqued? (Who can forget her claim that being an artist is being ‘just like shit in a clogged toilet, stubborn shit that can’t decide whether it wants to be flushed or to stick around, the shit that bobs up and down with hesitation.’7)

Womanifesto seem to make no such claim to the special status of the artist, and indeed your use of the term ‘collectivise’—is this a term they use too, I wonder?—aligns them with another ‘type’ of human, the worker, whose labour is thought of very differently from the artist’s. But what I like best about Womanifesto is their repeated refusal of labour, or rather, their recurrent insistence on the value of not-labour.

Nowadays, the kind of ‘retreat’ from not just urban, male-dominated hyper-productivity but also from labour—the kind of retreat that Womanifesto repeatedly initiated—appears in the form of youth movements-cum-hashtags like lie flat and let it rot, both from the Sinosphere. I’m drawn to this kind of nihilistic refusal of capitalist productivity. It’s not only women who need to rest. But can I say that, am I close enough to being in the same boat, oeeeeeeei?

Of course, Womanifesto’s collective projects, and their location in various rural sites, places them at least alongside if not ahead of better-known and more male-dominated counterparts in the region. But who else understood at this deep, bodily level the value of not doing anything—how generative this could be?

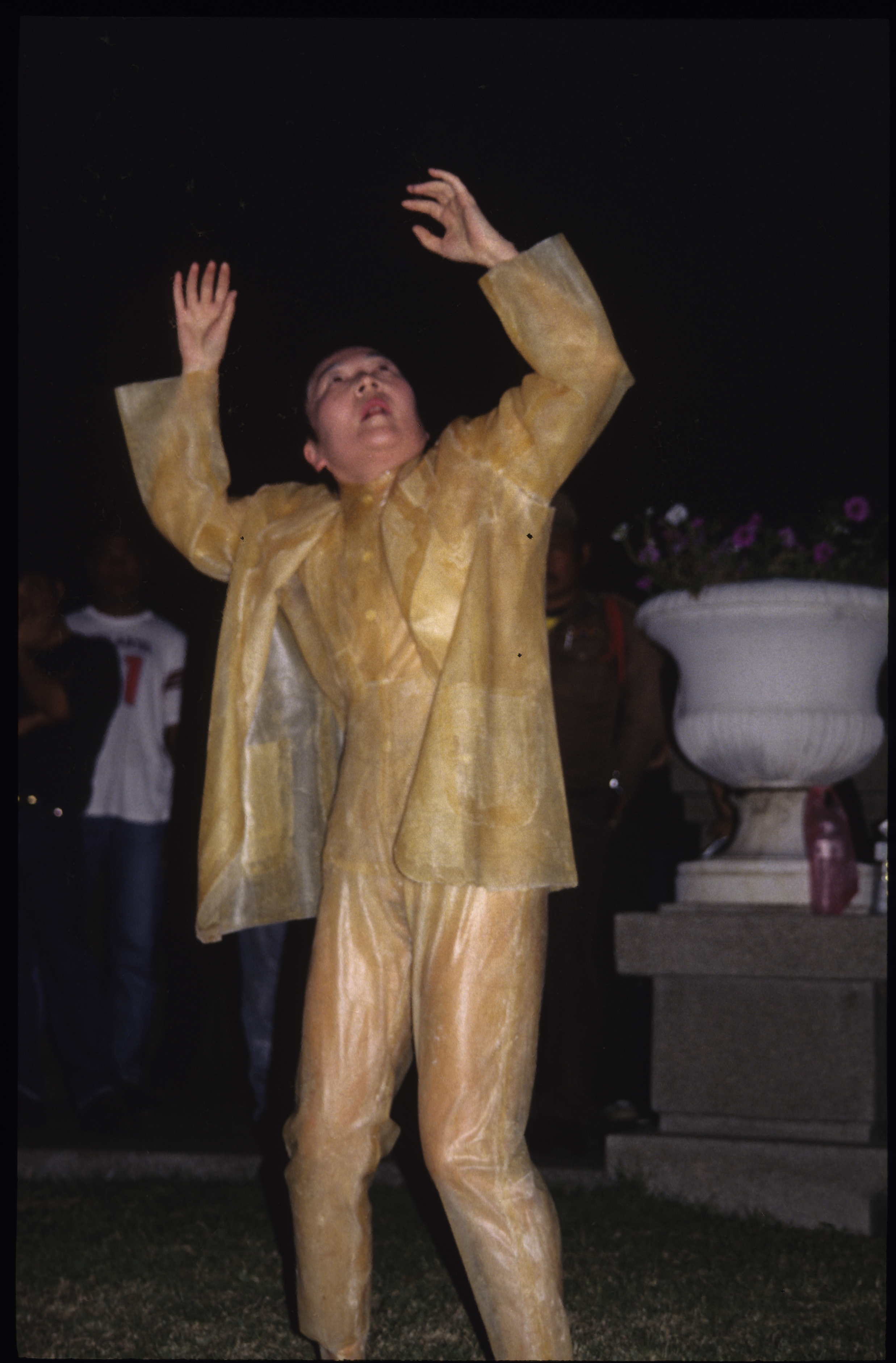

There’s this wonderful Tari Ito performance that I saw in the Womanifesto exhibition at BACC, where she emerges from a giant vagina. It’s an iterative performance, one she has done several times in several places. I’m not sure if the same giant vagina reappears, but I’d assume so, as it seemed well-made, and key to the work’s aesthetic. In a way, Womanifesto seems like that piece: able to be born and reborn, just for the sake of the dance and shimmy and exuberant energy of it all.

Is Tari Ito a doppelganger of Womanifesto, or are they both together a doppelganger of the animal essence—be born, eat, shit, die, repeat—that Araya forces into our vision?

MAI: And let’s not forget the other element in that cycle that still remains a special bind for female-human-animals. Was it the labour of care that necessitated the birthing of Womanifesto, Roger-oeeei? To be born, eat, shit, bring up young kin, care for debilitated and dying kin, get ill, die, repeat. What moves me about the refusal of art labour that you celebrate as the Womanifesto Way is that it seems to be simultaneously a strike (ha!) of a group of women against a world (art- or otherwise) whose self-perpetuation rests on invisible feminised labour, and a bet on what else could emerge if a group of women artists were to build together a time-space in which they could idle in the name of being a group of women artists.

Talking about refusing to comply with the kind of labour expected of us in a world not of our choosing reminds me of the atmosphere that drew me in, despite my initial wariness, during the recent exhibition ‘Womanifesto: Flowing Connections’. On paper the exhibition was yet another instance of belatedly canonising a select group of women artists through the convention of exhibition-making. Reading the exhibition text, I half-resigned myself to this possibility. One afternoon in 2024 I tagged along after curator Tang Fu Kuen to the eighth floor of that white spirally building. What I walked into I’m not sure I can quite put my finger on, but it felt a bit like an extended reunion, or a salon of some kind with an open invitation. Why limit your repertoire to solely delivering the career retrospective exhibition? Why not claim, as well, the authority to take up a lot of space right in the real/royal estate heartland of the entrepreneurial city, sit around there for some weeks, and receive a never-ending flow of friends and acquaintances, old and new, young and old? As the afternoon wore into evening, I was almost hoping one of the grey-headed art matriarchs would whip out a hidden pack of cards from her pocket and enjoin the rest of us women to form a circle for a few leisurely, nostalgic rounds of rummy.

RN: I spent hours in that exhibition, circling around and around the loopy BACC space. There were some artworks that captivated me—the kind that have stayed with me, that I’d like to write extensive close readings about—but it seems beside the point to dwell on any single artwork in the exhibition, just as it seems beside the point to think of Womanifesto as primarily about making objects. This is not to say that the artists involved have not made important and intelligent artworks, but that the practice of being together seems to be what really matters in the ‘Womanifesto way’, rather than the practice of making. Or rather, perhaps the practice of being together is a practice of making.

It’s taking a lot of self-restraint for me to resist the temptation to write about some of the artworks from the BACC show (or other Womanifesto exhibitions) in detail, not only because I love writing and reading close readings of artworks, but also because it’s the mode of art writing in which I feel most comfortable. I don’t feel all that comfortable or confident writing about the importance of being together. But maybe that discomfort is productive?

I think one of the things that I find most endlessly fascinating, challenging and significant in Araya’s practice as an artist-writer-educator is her evasive instability, her constant invention and invocation of more personas, more ‘Arayas’, so that it’s never quite clear who this person and artist and writer and educator and woman is, and who this ‘artmaker’ is. I value this not only because of the intellectual energy it offers, in relation to concepts as varied as the Buddhist non-self and queer multiplicity, but also because of the force with which it unsettles and dethrones the old, masculinist myth of the artist as genius. That myth of genius, of course, is always gendered as masculine and always coded as singular.

Perhaps one of the most exciting things I’ve been very grateful to gradually realise through the privileged process of learning from Womanifesto while working on this publication project is that they too are playing this game of toppling the myth of genius. Whereas Araya cultivates a generative instability or multiplicity of selves, Womanifesto insists on the collective nature of all artistry, indeed perhaps all humanity. The singularity required of the mythical genius has no place here. To do a close reading of an artwork made or exhibited during any of the Womanifesto projects would, I worry, be missing the point and reinstalling an idea of the artist as a singular figure, a kind of genius. It seems that Womanifesto teaches that the real intelligence lies in reliance, interdependence, togetherness.

MAI: Maybe another tough lesson we all need to learn from both Womanifesto and Araya is persistence through time, which is also a kind of insistence. Somehow this makes me think of a line by the novelist Yiyun Li that I once came across: ‘My refusal to be defined by the will of others is my one and only political statement.’8

1 Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook, ‘Mangosteen, a Male Stray called Toob Oei, and Womanimalifesto,’ Kong Rithdee (transl.), in Yvonne Low et al. (eds), The Womanifesto Way Digital Anthology, Power Publications, Sydney, 2025, Link to be added at a later date.

2 Yvonne Low and Roger Nelson, ‘Reflections: On Friendships and Beginnings (For Us, For Womanifesto),’ in Nitaya Ueareeworakul et al. (eds), Womanifesto: Flowing Connections, exhibition catalogue, Bangkok Art and Culture Centre, Bangkok, 2023, p. 68.

3 Araya, ‘Mangosteen, a Male Stray called Toob Oei, and Womanimalifesto’.

4 Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook, I Am An Artist (He Said), Kong Rithdee (transl.), National Gallery Singapore, Singapore, p.158.

5 Araya, I Am An Artist (He Said), p. 155.

6 Somporn Rodboon, ‘Voices of Womanifesto’, in Womanifesto, exhibition catalogue, 1997, unpaginated. Facsimile reproduced in Nitaya et al. (eds), Womanifesto: Flowing Connections, p. 60.

7 Araya, I Am An Artist (He Said), p. 8.

8 Quoted in Nan Z. Da, ‘Disambiguation, a Tragedy: The Diminishing Returns of Distinction-Making’ n+1, no. 38, Fall 2020, https://www.nplusonemag.com/issue-38/essays/disambiguation-a-tragedy/, viewed 9 October 2025.

May Adadol Ingawanij | เม อาดาดล อิงคะวณิช is a writer, curator, and teacher. Her writings and curatorial projects concern Southeast Asian contemporary art; artists cinema; de-centred histories and genealogies of cinematic arts; avant-garde legacies in Southeast Asia; forms of future-making in global majority artistic and curatorial practices; Southeast Asian artists moving image, art, and independent cinema. She is Professor of Cinematic Arts and Co-director of the Centre for Research and Education in Arts and Media, University of Westminster.

Roger Nelson is an art historian interested in the modern and contemporary art of Southeast Asia, and a curator at National Gallery Singapore. He was previously Postdoctoral Fellow at Nanyang Technological University and NTU CCA Singapore. Nelson is co-founding co-editor of Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia, a journal published by NUS Press. He completed his PhD at the University of Melbourne on Cambodian arts of the 20th and 21st centuries. Nelson has contributed essays to scholarly journals, as well as specialist art magazines such as Artforum, books, and exhibition catalogues. He has curated exhibitions and other projects in Australia, Cambodia, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. Nelson’s translation of Suon Sorin’s 1961 Khmer novel, A New Sun Rises Over the Old Land, will be published in 2019. His Modern Art of Southeast Asia: Introductions from A to Z was published in 2019.

Related pages

Share a Reflection

log in to share a reflection.