By Varsha Nair

Please note that this publication is currently under review and will be subject to changes.

This essay was first published in n.paradoxa volume 4 (July 1999) pp. 91-94.

‘Women are the hind legs of an elephant’, so goes an old Thai saying. Such poetic adages reinforcing patriarchal 'values' to constrain women, labelling them as followers rather than leaders, are one of the paradoxes confronting women living in 'modern' Asian societies. Another interpretation of the same saying can suggest the necessity of balance of all things in nature, animal and human—front and hind, hind and front—all moving in unison to secure normal function within and of any society. The hind legs, I am told, bear most of the weight of the elephant.

Challenging gender biases and questioning established attitudes, women artists have been forging a way ahead through the 1990s and becoming an active force to be reckoned with in many Asian countries. In this part of the globe, women's art organisations are still a somewhat alien concept. A women's art movement has not risen to the extent it has in the Western world. More recently however, women's art is beginning to take root and evolve, with more artists in Thailand and neighbouring countries taking the initiative to stage events at national and international levels. Through the 1990s increasing numbers of female students have been enrolling in art schools in Thailand and more women artists are working professionally. That there is little attempt from curators or galleries specifically to bring women artists together from the region, does not deter them from creating their own 'history'. Confronted with antiquated stereotypes and the usual misconceptions of what ‘women's art’ should be, Asian women artists aim to breakdown these preconceived notions and barriers through their individual practices and through shared experiences.

Concerted efforts are being made in this artistic world to interact and exchange, to become a unified force. The artists, donning the role of administrators, have seen the need to initiate and promote the process of staging group events—from organising, fund-raising, documenting and exhibiting their own works. As Pantini Chamnianwai puts it, Bangkok artists should get credit for being the first in Asia to establish this base.1

Womanifesto is in every way an artist-initiated event and our network has grown steadily in a direct way, mainly through personal contact and friendship. The group first came together in 1995 at an exhibition titled ‘Tradisexion’, which was supported by and held at Concrete House, an independent art space in Bangkok. This multi-disciplinary show featured painting, performance, installation and writings by six Thai women artists.

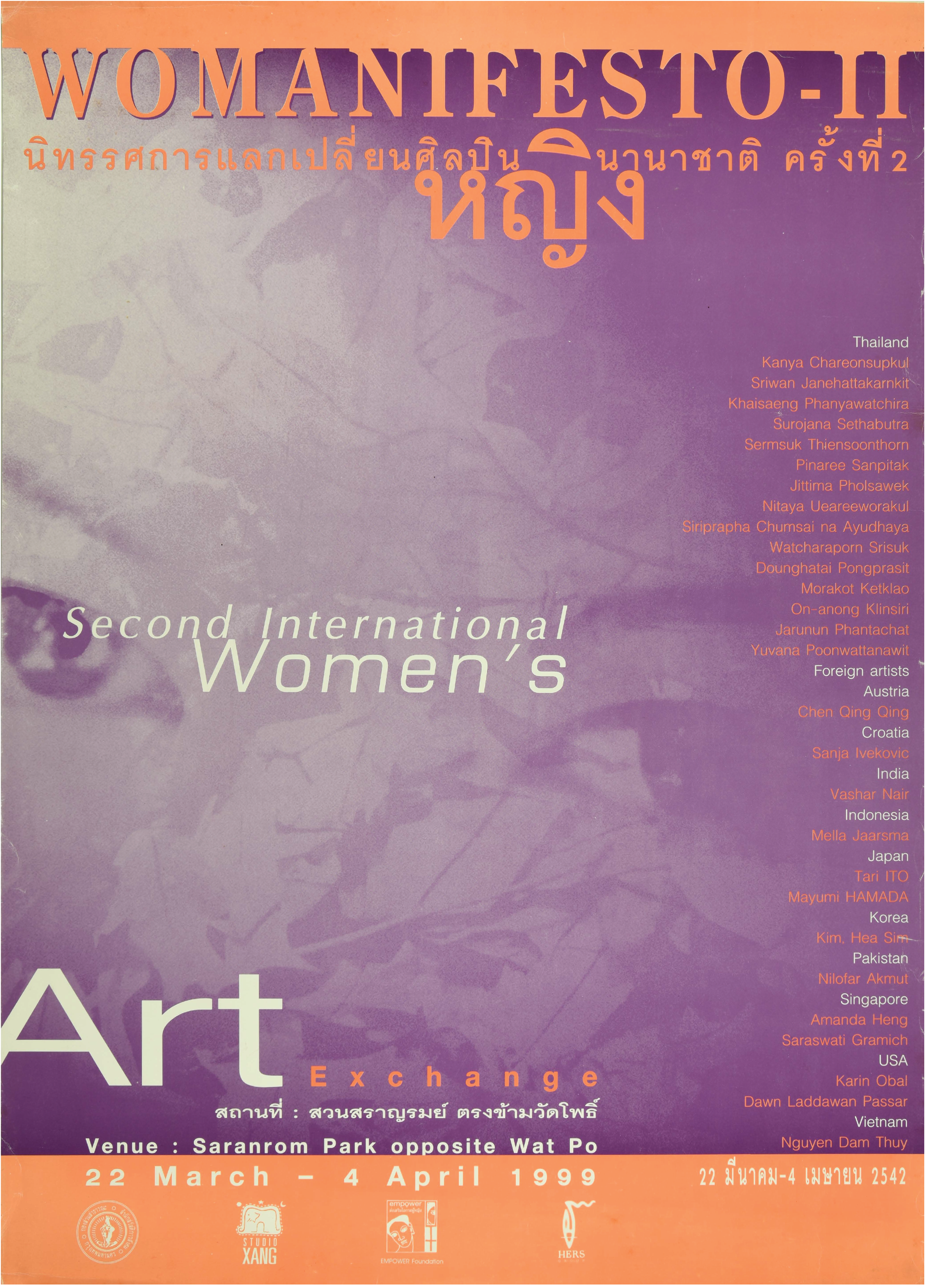

Co-organised by Thai painter Nitaya Ueareeworakul and myself, ‘Womanifesto I’ was held in 1997, and featured works by 18 artists—nine from Thailand and nine from Indonesia, India, Japan, Singapore, USA, Austria, Italy and Pakistan. Other larger art events in Thailand such as the yearly ‘Chiangmai Social Installation Project’ (now defunct) had fostered a meeting ground, providing a further point of contact. Many of the participating overseas artists at ‘Womanifesto I’ had previously presented their works in Thailand, either at ‘Chiangmai Social Installation Project’ or in exhibitions in Bangkok. Held in both Concrete House and the Baan Chao Phraya gallery (who also assisted in the administration of the project), ‘Womanifesto I’ was supported by Somporn Rodboon, lecturer of Art History at Silpakom University, who acted as advisor. Sponsored by private organisations and the Japan Foundation, ‘Womanifesto I’ received broad media coverage and was hailed as a 'new dimension' bringing women's art to the forefront.

‘Womanifesto II’ held this year (March 20–April 4 1999), incorporated a larger number of Thai and international women artists, consolidating its foundation and providing another rare opportunity for interaction. The key organiser Nitaya Ueareeworakul, was assisted by her partner Pantini Chamnianwai in their own art space—Studio Xang [elephant]. The event also supported by Duanghatai Pongprasit, a member of ‘Hers Group’—a group of young Thai graduates of the Silpakom University art school and the Empower Foundation, a non-governmental organisation involved in conducting education programmes for sex workers in the (in)famous Patpong area of Bangkok.

‘Womanifesto II’ has now gained further recognition as a vital 'meeting point'. This year it received total support from the Bangkok Metropolitan Authority (BMA) who have started in recent times to fund art events in public places, wanting to bring art into the open and make it accessible to a wider audience. The aim also is to establish Bangkok as the hub of freethinking artistic Asian scene. The BMA offered the use of Saranrom Park situated opposite the Grand Palace in the old historical part of Bangkok. A rare patch of green in the burgeoning metropolis of Bangkok, Saranrom Park at all time enjoys a 'full house', where jogging in single file on designated paths is popular and every day a lively well-attended pulsating aerobics session on a vast open stage begins sharply at 6 p.m. To the 33 artists that participated—17 from Thailand and 16 from Korea, Indonesia, China/Austria, Vietnam, Japan, USA, Pakistan, India, Australia, Croatia and Singapore, the location provided a ready audience.

Initially planned as a two-week workshop with emphasis laid on discussion and teamwork, artists were invited to collaborate or not with each other to create works on the spot and the exhibition was scheduled to stay on site for a period of one week. Budgetary constraints from the beginning however resulted in the cutting back of the workshop period to one week, forcing most of the participants to 'pre-plan' and in some cases, realise a major part of their works beforehand, with only a few artists beginning the process after visiting the site. During the week artists presented slides and talked about their work and a conference was planned on the second day following the workshop and opening of the exhibition. All were open to input from the public and at the first meeting in the park, artists selected locations for their works. An indoor space in 'the glass house' where the conference was held remained unused, as all artists preferred to exhibit outdoors. An enthusiastic and capable group of volunteers were available to mediate (Thai being the only language spoken in many situations), to aid the artists in seeking out materials, equipment and in helping to install the works.

With no given theme to the event, the artists presented works addressing a broad range of individual concerns. Offering an 'open-minded' platform, Thailand provides neutral ground to some of the visiting artists, who would find it difficult to show their work in their respective countries. Amanda Heng from Singapore works mainly in the performance medium, which in her native Singapore is not favourably looked upon. All material must be vetted and 'passed' (censored?) by the authorities. Performance artists are also perceived as problematic in communist Vietnam.

Nilofar Akmut's work, which explores Pakistan's turbulent political history, would almost certainly result in dire consequences if shown in her native Pakistan. (Also the recent nuclear muscle-flexing and increased animosity between neighbours Pakistan and India where I was brought up, makes it almost impossible for artists to meet despite shared historical background, limiting or even denying any interaction.) A part of a larger work in progress, Nilofar's Head Facing? explores the artist's experience of growing up under a military regime in Pakistan and living in the West. Her past work has also researched the history of partitioning of the sub-continent, particularly examining the women's movement that ensued at that time. In the accompanying text for Head Facing? Akmut re-iterates on growing up without an image and turning to the West (she spent 20 years overseas). ‘Some nations pour volumes of concrete to bury their past. Mine, directs a pistol to silence me.’2 Exploring the space between the political and personal, she constructs out of wood, perspex and welded metal, box-like structures—one resembling a prison or a cage complete with metal bars. A skewered cast metal 'head-like' form rests on a box frame which also contains a light-box housing a photograph of a woman with calligraphy drawn on her chest, holding miniature tanks, hair drawn forward covering her face. The feeling of entering a highly personal space that simultaneously denies access is reinforced by her choice of locating the work in a secluded leafy comer of the park.

Visiting the East for the first time, Sanja Ivecovic from Croatia realised a collaborative workshop at the Bangkok Emergency House, a shelter for abused women, in her work titled Pavilion 8, The Bangkok Emergency House Project.3 Part of an ongoing project, she has conducted similar workshops in other countries giving visibility to the invisible—women that are seeking refuge and are ‘hidden’ from society.4 For the Bangkok part of her work in progress, Sanja moulded facemasks of eight of the women, most are HIV positive, and installed them on top of pillars of the octagonal band-pavilion. Poignant texts written by each of the women highlighting their individual situations, were placed below.

Thai artist On-Anong Klinsiri, a recent graduate of Silpakom University, installed Boudoir 2000, an interactive mixed media work in another pavilion. Addressing the confusing 'war' between traditional and imported cultures, an innovative 'boudoir' was constructed from objects resembling sandbags—stockings and other diaphanous material of various sizes (a material she has successfully employed in the past to create large installations), were stuffed, stitched and placed to create a circular 'bunker' with a transformed padded jukebox cocooned at its centre. On inserting a coin, the viewer was played a recording of women reciting traditional Thai proverbs about women and their role in society. In creating this personal space to help locate her self, On-Anong explained that the sandbags were placed to hide behind, in order to absorb old culture or to react to something coming at you.5

Working within rural farming communities, Jittima Pholsawek, a Thai writer and performance artists, addresses gender issues and environmental concerns through her performance titled The Arrival of Death—Natural resource management in the central plain fanning of Thailand. With a group of artists and members of non-governmental organisations, Pholsawek has been an active campaigner against the building of a dam in Northern Thailand. Her experience of life in this rural society where all female and male energies are focused on tending and living from the land, the very destruction of their environment spells the same fate, regardless of gender, for the whole community. Through the recital of her poem accompanied by projected visuals of life supported by a river, she tells the story of the river in form of sound created with stones and bamboo until the concrete and iron cuts the river to.6

Yin-Yang an installation by Nguyen Dam Thuy explored the harmony between nature and the human body by placing scarecrows made from bamboo, black cloth and Vietnamese farmers' hats and creating white pebble square 'earth' and round 'sky' shaped boundaries around them. Although creating an unusual sight in a manicured park, locating the work indoors would have been beneficial in further decontextualising the subject in extending into abstract thought. Focusing on the spiritual, Ko Hyun-Hee (Korea) created a visually strong image in Sun, Strings & me. She tied yellow strings to the branches of a tree, beyond which the spires of Wat Po (the temple of the reclining Buddha) are visible, leaving them to trail on the grassy bank as if taking aerial roots. Hyun-Hee's 'new' form must adapt to co-exist with the environs of the city. 'Yellow', so much a part of Buddhist ritual, is considered the colour of life. On sultry April days, the tree aided by the strings took on an ephemeral quality, swaying in the lightest of breezes and communicating a spiritual life force.

The discussions at the ‘Womanifesto II’ conference centred around the future planning and direction of the event. Clearly one day assigned to debate was not enough to allow for individual experiences to be shared with the group as a whole. Personally, the informal gatherings that took place during ‘Womanifesto I’ in one of our homes, where individual concerns were aired and discussed at length, made for a more meaningful and lively exchange. Most agreed that such a meeting provided a rare opportunity to share and develop collaborative works and working in smaller groups would provide a greater possibility of interaction, although a longer workshop/residency period would be more beneficial. A suggestion that future exhibitions should take on a more thematic approach received divided responses with some artists appreciating the freedom to create their work without the parameters of a 'theme', while others felt that it was too loosely based. The Thai organisers were open to ideas and voiced their interest in having participating artists hosting the event in their respective countries in the future. All felt strongly about remaining totally independent and to avoid being dictated to by governmental, non-governmental or any sponsoring institutions. The lack of a regional 'women's art organisation' to enable artists to network was discussed. A decision was made to fund and establish an archive of women's art, which would be compiled initially from the information provided by the participants of Womanifesto. Womanifesto aims to become an established event and to gain momentum to project itself well into the future. Nitaya Ueareeworakul plans to leave Bangkok and return to her home in Northern Thailand, where a long-term aim is to set up a women's art centre and invite artists in small numbers for workshops or residencies on a continuous basis. The BMA has pledged its support for ‘Womanifesto III’ but before doing so they would need to gain more of an understanding of how to support artists and promote 'art'. Setting up a clearer system to aid artists in managing such projects would be a start. Currently any government funding is only given long after the completion of an event and after negotiating the inevitable 'red-tape' labyrinth, forcing organisers to struggle to find monies beforehand. Symbolic of this gathering in aiming to open avenues and broaden the horizon, Thai artist Sermsuk Thiensoonthorn placed a gate across the main jogging path of Saranrom Park, stimulating individual action and prompting both participants and viewers to open, enter and be part of it all.

1 Citation needed here.

2 Nilofar Akmut, “Head facing?’, in Studio Xang (eds.), Womanifesto II: Second International Women’s Art Exchange, exhibition catalogue, Saranom Park, Bangkok, 1999, unpaginated.

3 See XXXXXXXXXXXXX, ‘XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX’, n.paradoxa, vol. 4, 1999, pp.42–44.

4 See Sanja Ivecovic, ‘Pavillion 8, The Bangkok Emergency House Project’, in Studio Xang (eds.), Womanifesto II: Second International Women’s Art Exchange, exhibition catalogue, Saranom Park, Bangkok, 1999, unpaginated.

5 citation needed.

6 citation needed.

Related pages

Share a Reflection

log in to share a reflection.