By Penwadee Nophaket Manont

Translated by Pojanut Suthipinittharm

Please note that this publication is currently under review and will be subject to changes.

‘At Womanifesto, we value relationships more than the end products.’

Nitaya Ueareeworakul, co-founder of Womanifesto

8 March 2023, Womanifesto House, Udon Thani

—

I began my career in the 1990s, as the twentieth century was drawing to a close and at a time when ‘contemporary art’ was just emerging in Thailand, disrupting the boundaries of our conventional artistic practices. I got to experience first-hand that pivotal shift in the artistic circle, and the experience has informed my work as an independent curator to this day.

Looking back on my experiences when I was still experimenting and exploring things to see what I was meant to do, I think my interest in art began in my formative years growing up in a politician’s family, surrounded by questions of social problems. The openness of the artistic circle in the 1990s gave me the courage to create new opportunities for myself, to make a career out of what I was interested in, with works that reflected socio-political issues through individual, communal and structural perspectives. I was allowed to start my career as a curator with a clear and specific ideological and political stance without having to cater to anyone. The most challenging part was my eventual decision to work in a variety of art spaces and not just confine myself to the comfort of the capital city.

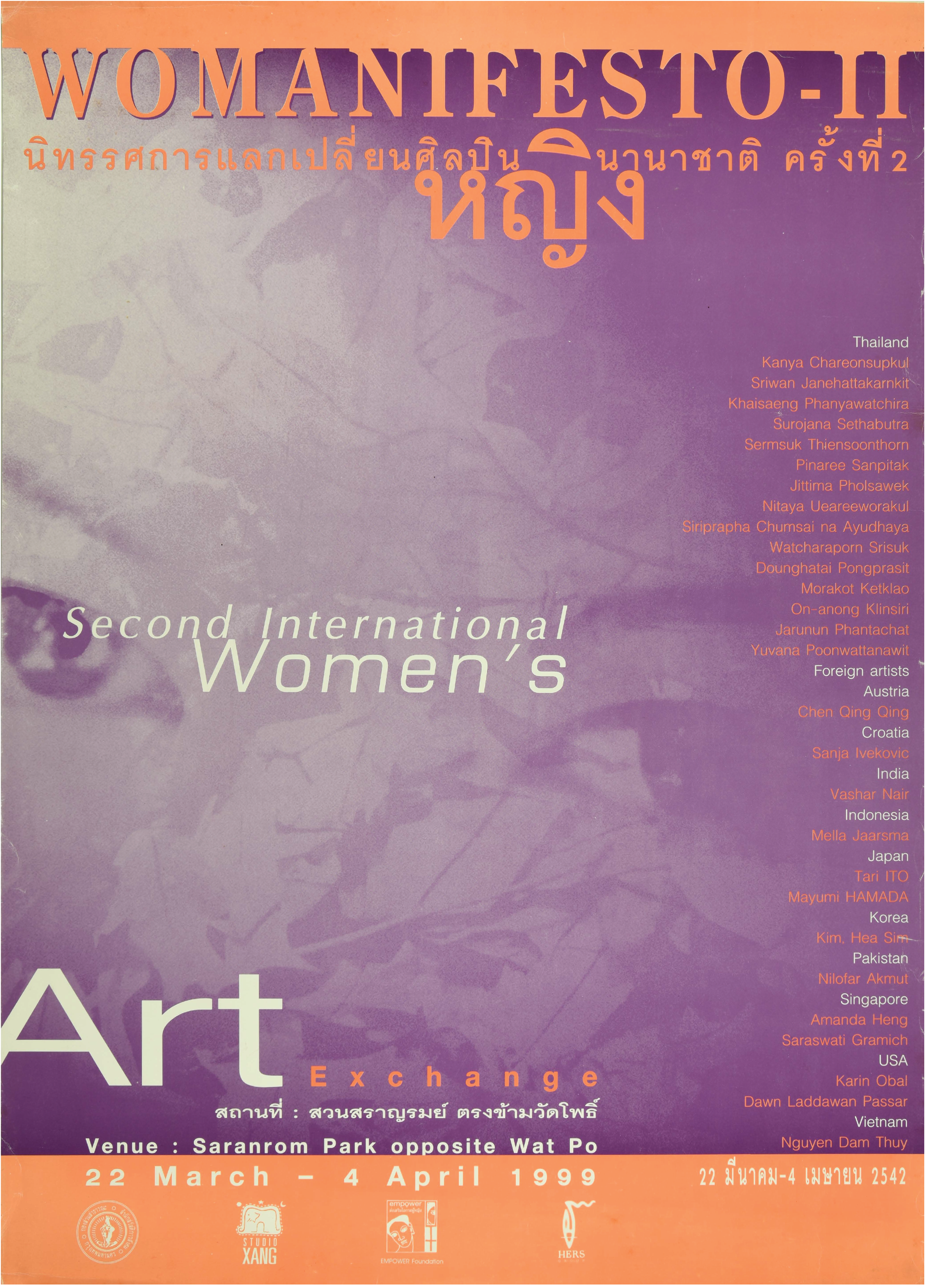

I consider myself lucky that today I’m able to do the job I love. This was possible because I had gained a range of different experiences across a spectrum of independent projects. During my first foray into the art world, I recognised many opportunities for utilising alternative art spaces such as Project 304, Marsi Gallery (Suan Pakkad Palace) and Studio Xang. Eventually, in 1999, I got the chance to take part in the ‘Womanifesto II’ project in collaboration with Studio Xang as a volunteer and was assigned to work as an assistant to the Croatian artist Sanja Iveković.

Me :: Contemporary Art Practices and People’s Perception

Pavilion 8, The Bangkok Emergency House Project, by Sanja Iveković, was part of a long-term international project started in 1998 under the moniker ‘Women’s House’. It included site-specific installations developed through a workshop with eight women who were seeking refuge at a local shelter called ‘Bangkok Emergency House’. These women were victims of domestic violence and other forms of abuse, and they, as well as the Bangkok Emergency House staff, kindly agreed to collaborate with the artist for the project.

The following is one of their stories:

I got the disease from my husband nine years ago. I have a child. He’s seven years old. It is my luck that he did not catch the disease. My husband has already passed away. The reason I came to live at this Emergency House was that some of my brothers, sisters and relatives thought me disgusting because of the virus. But some understood and they took good care of me as if I were a normal patient. That made me want to live longer. I hope there will be a vaccine that can cure this disease in the very near future.1

While serving as one of the artist assistants for Iveković in the Pavilion 8, The Bangkok Emergency House Project, I unexpectedly found myself tasked with liaising with a woman with HIV. This experience propelled me into an intensive study of the disease, from its symptoms and transmission rates all the way to treatment options for both physical and mental wellbeing. I overcame my own fear and looked at the facts. It was a process of expanding my own horizons through an engagement with a contemporary artwork deeply rooted in social concerns. The work communicated its message and challenged the perception of both the project’s participants and its audience. This valuable learning experience underscored for me the significance of process within contemporary art practices, illuminating how it organically fosters meaningful exchanges of knowledge and understanding.

Womanifesto :: The Journey and the Alternative

During my recent discussion with Nitaya Ueareeworakul, one of the co-founders of Womanifesto, I learned that the program originated during a gathering at the Baan Tuek Art Center in Bangkok. This centre serves as an alternative art space for progressive artists dedicated to creating socially, culturally and politically conscious art. In 1995, the centre held an exhibition called ‘TradiSEXion’, and this was the first time that female artists had the opportunity to tell the varied stories of inequalities faced by women through different artistic mediums like painting, writing, poetry, installation art and performance art. Even though the event was criticised by art critics and journalists at the time, the founders were undaunted. They continued to work according to their convictions, and later formed relationships with international artists who had come to participate in the Chiang Mai Social Installation Festival. After that, in 1997, the international program for female artists ‘Womanifesto I’ was organised at the Baan Tuek Art Center and at Arts Gallery at Ban Chao Phraya. In 1999, ‘Womanifesto II’ was held at the Saranrom Park. Both ‘Womanifesto I’ and ‘Womanifesto II’ were based in Bangkok in collaboration with a network of Thai and international artists and consisted of both artistic works and performances. The events were funded by Thai and international institutions and allowed a new generation of female artists to gain notice, as well as encouraged intergenerational collaborations between them.

The indoor exhibition ‘Womanifesto I’ and its open-air counterpart, ‘Womanifesto II’, elicited notably different responses and manners of participation from both participants and audience members. This led to the idea to change things up again for the international ‘Womanifesto Workshop 2001’, where the project left Bangkok for the first time. The event was held at the Boon Bandarn Farm in the north-eastern (Isan) province of Si Saket. The point of the workshop was to allow local craftspeople, children, teenagers, adults, and the Thai and international artists and independent curators to come together and exchange skills and ideas, sharing ways of life and contemporary art practices. The results of the project were thus highly distinct from the first two exhibitions. The artists gained a first-hand experience of the Isan way of life. The local art and culture and the simplicity of the Isan people’s way of life became the thematic focus for the organisers, and the participants formed genuine friendships with each other in a natural way through this alternative art space.

The friendships among the organising team endured and grew into the fourth Womanifesto in 2003. This edition marked another significant evolution as the format was yet again adapted to suit the prevailing circumstances of the participants at the time. This time, it became a print project under the title ‘Procreation/Postcreation’, inspired by a recent episode in the life of one of the organisers who had just given birth to a baby daughter and, therefore, couldn’t participate in any live event. The rest of the team thus decided to base the project on this real-life event instead. Many international artists, both male and female, agreed to take part in the project, and it proved a terrific success. The fifth installment of Womanifesto was an online website project under the title ‘No Man’s Land’, an imaginary borderless scape free from private ownership, inspired once again by the life of an organising team member who was born, grew up and lived all in different places—a borderless life. Then in 2008, as lives converged again, the team managed to organise the program together in person, resulting in the sixth Womanifesto event, a residency program at Boon Bandarn Farm in Si Saket. This residency program for international female artists extended an invitation to a local folk artist to join as an artist-in-residence alongside four other contemporary Thai and international artists over a period of 20 days. The local artist’s participation allowed for a cultural exchange of local handcraft skills which are integral to Isan’s way of life. There was also a workshop with children and teenagers, an element which has been part of Womanifesto’s mission for many years.

Nitaya revealed to me that the co-founders of Womanifesto were friends before becoming co-workers. Thus, they allowed each other the freedom to choose the method and process each preferred, so each could create their own opportunities without having to wait for another’s approval. Additionally, no one was in it for the fame. As a result, they enjoyed the work more and were able to establish new friendships along the way, like during the residency project where the invited artists stayed over at an organiser’s home. These friendships emerged organically and enabled wonderful exchanges to take place. Certainly, there were occasional disagreements, but Womanifesto has always prioritised the sharing of the creative process over striving for a flawless end product. The group placed a strong emphasis on learning through interactions and meaningful conversations. In moments when certain members required a break from the group’s activities due to personal circumstances, others readily stepped in to fill their roles.

Womanifesto has demonstrated to me that the process of artistic creation doesn’t always have to involve sensational declarations—like the ones that attracted criticisms during the ‘TradiSEXion’ exhibition in 1995—but contemporary art practices can also manifest in the gradual changes in people’s lives, serving as historical records of life journeys and evolving relationships among friends.

Me :: Check and Balance

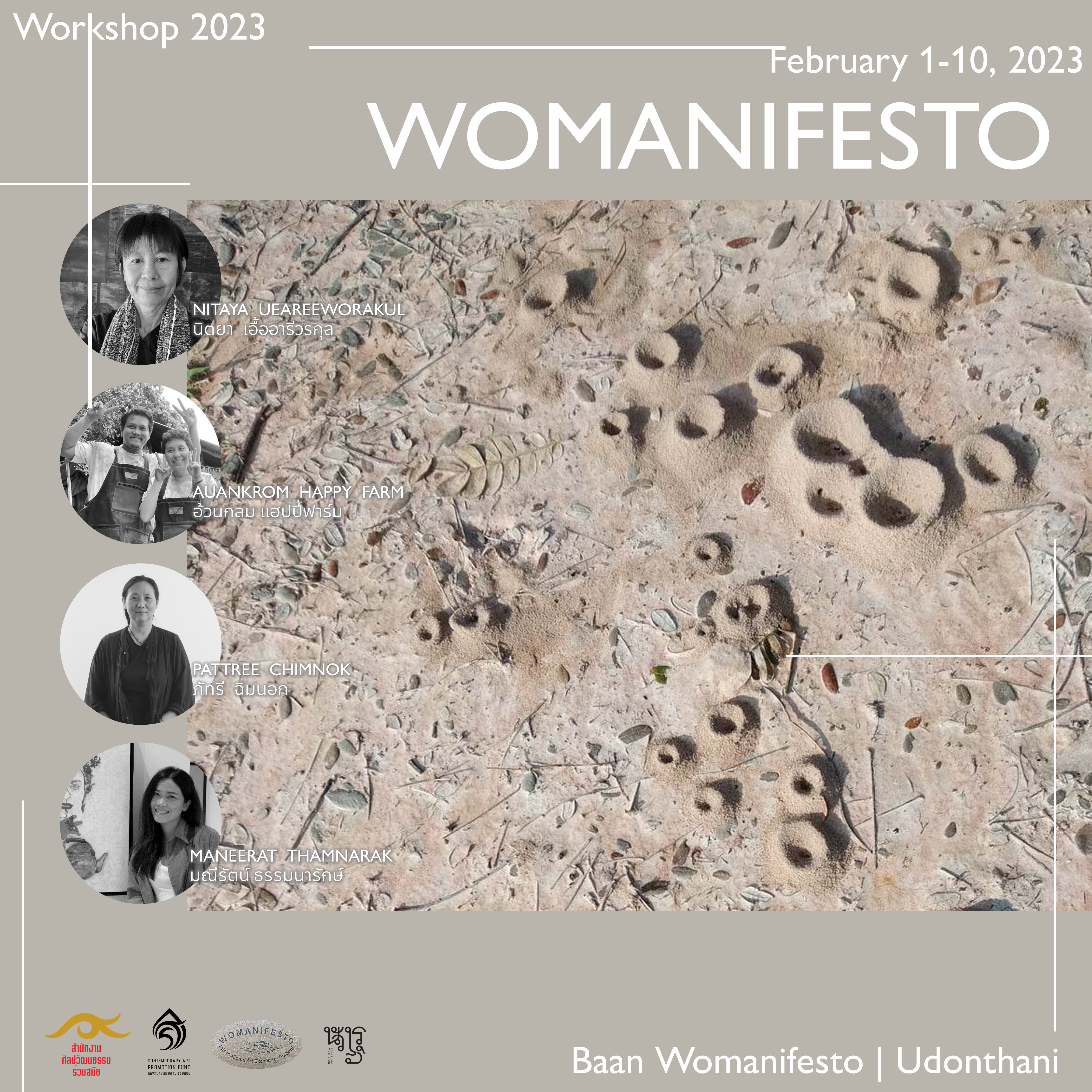

Reviewing my past experiences, particularly the fieldwork with ‘Womanisfesto Workshop 2023’ at Womanifesto House in Udon Thani, I now recognise more clearly than ever that the alternative art spaces I engaged with during the 1990s inspired me to challenge conventional boundaries as an independent curator. During the workshop, I got to learn about the importance of the process in contemporary art practices and expand beyond the white cube exhibition rooms. I witnessed how cooperations between different generations, regions, religions and cultures can sow new seeds in the thoughts of newer generations. Opportunities were not limited to any particular location or group. The creative process I saw was based on the idea of limitless freedom for the artists to create their work.

‘Womanifesto Workshop 2023’ was held from 1 to 10 February 2023 at the Womanifesto House in Kumphawapi district, Udon Thani province. The 10-day event was an opening up of Nitaya’s family house on a 40-acre property for non-local artists to come and exchange their knowledge and experience in the context of the upper Isan region. The final day was an open day with workshops running for high-school and university students from the same province or from neighboring towns. Supported by the Office of Contemporary Art and Culture, Ministry of Culture (OCAC) Art Fund, the artists who participated in the project included Pattree Chimnok (Chiang Rai), Maneerat Thamnarak (Chumphon), Uan Klom Happy Farm (Udon Thani), and Nitaya Ueareeworakul (Udon Thani), plus their assistants Adisak Phupa (Maha Sarakham) and Surasit Mankhong (Udon Thani).

‘Womanifesto Workshop 2023’ focused on exploring different neighborhoods of Udon Thani province. People shared their life stories while living together, and the artists were challenged to adapt to their new environment while collaborating with each other throughout the project with various activities. These include visits to the Ho Chi Minh Historical Site, Ban Chiang National Museum and Ban Chiang Pottery Community Enterprise; a workshop at Uan Klom Happy Farm; a visit to a learning centre for natural fabric dyeing; and an exchange session between the participating artists and a group of young artists from NOIR ROW ART SPACE. During the session, Isan artists from Maha Sarakham and Udon Thani shared local knowledge of clay and ceramic works.

The field trips, integral to the ‘Womanifesto Workshop 2023’, served as a reminder of the significance of process within alternative contemporary art projects and of extending beyond the confines of indoor exhibition spaces. The trips facilitated the sharing of knowledge and experience with rural communities, prompting artists from diverse backgrounds to establish new networks and apply contemporary practices to their respective local contexts.

The journey of an observer like me from the capital city up to Udon Thani, where the Womanifesto project was held, also reminded me of my own evolution as an independent curator over the past decade. It brought to mind my steadfast commitment to exploring socio-political themes through the lenses of individual, communal and structural perspectives within contemporary art practices. The exchanges between the artists and the use of alternative art spaces enabled new explorations and new possibilities for breaking down rigid barriers. Additionally, they fostered mutual understanding between different social and cultural contexts, resulting in powerful expressions of marginalised experiences and of the small lessons we learned together over that period.

Me :: Embracing the Alternative in Contemporary Art

Alternative art can be defined in various ways depending on the practice of a given artist or curator. The term often suggests a manner of artistic creation that presents a different alternative to the conventional—one that differs from the popular trends, the conventional styles, or the commercial approaches. Most alternative art doesn’t conform to the usual standard of practices that the society or prominent artistic circles may determine but is often born out of individual creativity.

Hence, an alternative artwork may not fit well with other art pieces in the conventional exhibition space or museum rooms. It may emphasise socio-political views, environmental issues, or important issues to art and society. Its format is also varied, including but not limited to:

- Works that challenge the existing norms by inventing new ideas or creative processes.

- Works that exert their freedom of expression without being limited by conventions or trends.

- Works that employ simple, local or everyday materials to create specificity and uniqueness for the art work.

- Works that emphasise the creative process and cooperations, valuing the stories behind the work over the artistic end products, and treating the collaborations and sharing of ideas as an integral part to the creative process.

- Works that serve to link people and communities, often occurring in communities or among groups of people with like-minded views about what art should achieve.

Overall, alternative art celebrates diversity. It presents an alternative that allows more freedom of expression for the artists, the curators, and the creators. It helps facilitate interactions, form relationships, and connect communities and groups of people who share similar interests, beliefs or goals, all in order to convey meaningful messages for the society, the culture, or even our politics.

Me :: The Conditions for Freedom

In 2012, I left my full-time job of five years as a member of the curatorial team at the Jim Thompson Art Center, where I had gained many valuable experiences and opportunities. I was looking to tackle the problem of my freedom as a curator, to fulfill the conditions that would allow me to fully determine my own direction. During my first foray as an independent curator, I allowed myself the chance to explore different types of work with the hope of finding the type of contemporary art to which I would be ready to commit myself long-term. Three international art projects came my way, and I worked as the Project Manager of ‘THAI-TAI: A Measure of Understanding’, a contemporary art exhibition/research project/workshop between Thailand and Taiwan; the curator for the contemporary art exhibition ‘Poperomia / Golden Teardrop’ in the Thai Pavilion at the 55th International Art Exhibition—La Biennale di Venezia (Italy); and the curator of educational activities, film programs and seminars for the Bangkok ASEAN Art & Culture Festival held at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre (BACC) in early 2014, amidst political unrests on the streets of Bangkok.

‘Shutdown Bangkok’ was an anti-government rally organised by the People's Democratic Reform Committee (PDRC) which lasted from January 13 to March 2, 2014. The movement’s aim was to oust Ms Yingluck Shinawatra, the then–prime minister of the interim government. The PDRC additionally demanded thorough political reform take place before the general election could be held on February 2, 2014. This shutdown tactic of the group was an escalation from its ‘starburst’ protest strategy which it had employed since November 2013. ‘Shutdown Bangkok’ was also a takeover of the capital city of Bangkok, home to all the main government organisations, in order to signal to the world that Thailand was then a failed state. The founding of the PDRC on November 29, 2013—with allies in the Network of Students and People for Reform of Thailand (NPRST), a group of academics; Silom Business Association; Dhamma Team; Anti-Thaksin People’s Army; State Enterprises Workers’ Relations Confederation (SERC); former Democrat Party MPs; and with Suthep Thaugsuban as the secretary-general of the PDRC—meant that the anti-government movement could gain a more unified momentum. On December 22, 2013, the PDRC organised large anti-government rallies on Ratchadamnoen Avenue, Petchaburi road, Asoke intersection, Uruphong intersection, Pathumwan intersection, Ratchaprasong intersection, Lumpini Park, and the Victory Monument, essentially shutting down Bangkok for half a day. Mr Sonthiyan Chunruthainaitham, a leader of PDRC, claimed that ‘On the 22nd of December 2013, over 5 million people gathered en masse and marched on the streets to demand reforms before the coming election.’2 Then on the night of December 27, 2013, Suthep declared on the stage that ‘after New Year’s Day, we’ll reconvene here to take over Bangkok. It will be a complete take-over to restore sovereignty back to the people.’3

On December 28, 2013, I decided to contact many of my friends in the contemporary art scene, the film industry and academia, as well as independent media, to set up an alliance to insist on people’s rights to have a general election as scheduled on February 2, 2014. At that point, the ANTs’ POWER art and culture group was set up and we organised happening art flash mobs which included the following:

- The ‘Let’s Go to the Polls’ activity where people gathered wearing white and released white balloons as a symbolic gesture on Sunday January 5, 2014.

- The ‘Vote as You Like’ activity where election booths were set up to simulate a clean and fair election where the people could choose the party they like or tick ‘no vote’ freely. This event was held on January 10 on the Skywalk between Siam Discovery and the National Stadium BTS station. It was meant as a platform for the people to express their desire for their basic rights to be respected and for a fair and effective screening and monitoring of politicians.

- An activity promoting a peaceful election on January 31, 2014, inspired by ‘Bed-in for Peace’ by John Lennon and Yoko Ono in 1969. We prepared a bed and a blanket along with papers and pens for participants to express their desire to walk up to the election booth in peace. The activity reflected the importance of human freedom and equality and was organised on the Skywalk bridge at Chong Nonsi BTS station.

During the final days before the election on February 2, we sensed a growing threat to a fair democratic election under the constitution because the Election Commission of Thailand had made it clear that they were unwilling to fulfil their responsibilities to protect the electoral process. Therefore, we decided to seek the help of the Internal Security Affairs Bureau and the Center for Maintaining Peace and Order to help protect election booths. The ANTs’ POWER group also invited allies within its network, including the groups Por Khan Tee (พอกันที) and WE VOTE, to help bring more than 3000 postcards from our ‘Vote as You Like’ campaign to General Nipat Thonglek, the then–Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Defence, to insist on the people’s will to have their basic rights be respected on February 2 without threats of harm or violence. Our network demanded that police and military personnel, as well as the Civil Defence Volunteers, be mobilised to help protect against violence and other threats to the democratic process, so that the Thai citizens could safely access the election polls in their district throughout the country.

As it turned out, our fear about election day was not far off. On March 31, following a request from the Office of the Ombudsman, the Thai Constitutional Court nullified the February 2 general election. The verdict was based on the claim that twenty-eight constituencies failed to hold voting on that day. In a 6-3 vote, the court determined that the February 2 general election was unconstitutional, due to the failure to hold a nationwide general election within a single day.4

Later in 2014, ANTs’ POWER, Por Khan Tee, WE VOTE and other groups formed a new alliance to continue our activism under the name of Project HOPE, led by the Citizen for HOPE network. Our aim was to work out a solution for Thailand through democratic, law-abiding and constitutional means, while respecting everyone’s freedom of speech and avoiding conflicts. Project HOPE continuously organised activities up until the 2014 coup by the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) on Thursday May 22, led by General Prayut Chan-o-cha. The NCPO overthrew the interim government of Niwatthamrong Boonsongpaisan, who was the caretaker prime minister following Yingluck Shinawatra’s removal by the Constitutional Court. This was the 13th coup d’état to take place in Thailand, and after that, the country’s democratic system was placed under severe control. Thailand fell under a hybrid political system that was only half democratic, with the other half a dictatorship.5

Then, in mid-2015, a member in our Citizen for HOPE network received a bomb threat in a call to his house where he was living with his elderly parents. The caller told him to stop anti-junta activities. Upon deliberation, our group decided to cease our activity to protect everyone’s safety. The coup also deprived many of the citizens of their rights, and the military institutions were able to increase their power over Thai politics. Independent political expressions from the various groups almost completely disappeared, with some going underground. Unsurprisingly, artists and curators were also unable to make their political opinions heard in a direct way during that period. Then in 2016 came a big turning point for me as an independent curator. Under this climate of oppression, I was more than ever interested in political issues and was selected to participate in the Arts Initiative Tokyo (AIT) Residency Programin Japan from February 22 to March 26, 2016. Thai artists, authors and I (as a curator) got a chance to present our views on the political conflicts in Thailand in an event called ‘A Roundtable with Artists and Other Guests from Thailand’ on Saturday March 12, 2016, supported by the Agency for Cultural Affairs, Government of Japan (Bunkacho).

In mid-2016, we began preparations for the contemporary art exhibition ‘Condemned to be Free’, which explored, questioned and criticised the recent period of social and political turmoil in Thailand through the philosophy of Jean-Paul Sartre. The exhibition was held from February 15 to March 31, 2017, at the WTF Gallery in Bangkok. In the same year, another contemporary art exhibition, ‘The Enmeshed’, was organised, presenting selected works created through research into the socio-political situation in the three southernmost provinces of Thailand. The exhibition recorded and conveyed the multicultural experiences of the locals in an area which had so often been portrayed in the mainstream media through images of violence and unrest. This exhibition was shown at the Art Centre, Silpakorn University in 2017 and then at A+ Works of Art Gallery in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, in 2019.

As I’ve mentioned, it can be said that 2016 was an important turning point for me as an independent curator. I got the chance to have my say on a global stage to a receptive audience regarding the political conflicts in Thailand during a period when most people in the country were being restricted in their freedom of expression. Many members of the audience expressed their surprise over the complexity of the Thai political context, and there were many questions and much interest from both the people in the art world and the general audience. That experience gave me the confidence that the approach I was exploring and the topics I wished to study, explore and record in contemporary art were possible. That same year was also the year I founded Rai.D Collective, a collective of curators and cultural managers, with the aim to organise contemporary art exhibitions and conduct research projects relating to socio-political and cultural issues. Not long afterwards, while preparing for the ‘Condemned to be Free’ exhibition in 2016, I was introduced to the works of artists from the three southernmost provinces of Thailand, and this led to my being involved in practice-led research in that area to this day.

Another big turning point occurred not long after the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Thailand. In the beginning of 2020, I had a moment to reflect on my own work as an independent curator up to that point, especially reviewing the experience of research field trips into the three southernmost Thai provinces. What stood out to me was a very clear picture of the inequality that exists in Thailand. People in the capital city of Bangkok have access to many more opportunities compared to the people in marginal spaces. This inspired me to want to continue what I was doing and to challenge myself with a novel set of objectives and approaches to my work. I was hoping to promote the decentralisation of power, opportunities and knowledge in contemporary art, ensuring it reached those on the margins. Not only that, I was also hoping to engage in an alternative kind of curatorship to advance different issues outside the traditional exhibition spaces. I started discussions with fellow curators and soon afterwards founded Project-PRY within the same year.

The collaborative project was born out of a conversation between contemporary art curators about how we were to survive both the pandemic and the political turmoil in the country. We wanted our work to tackle socio-political issues through interactions with real communities and expand the ecosystem of art beyond its traditional box. We hoped more than anything that, once curators and artists embedded themselves into real communities in creating their work, we would be able to drive social changes, starting from small social units. In ‘Project-PRY #1’, we got the chance to work with Isan artists for the whole latter half of 2020. We went to conduct field research in Maha Sarakham province for the first time and were able to tell the stories of the Isan people who lived under a centralised rule by elites in the capital city. We collaborated with community members to convey the vitality of their daily lives, despite being constrained by a biased social structure, limited choices, and restricted opportunities to realise their dreams, as well as the inevitable distortion of community values. From that point, field research in the Northeast began and continues to this day.

Nevertheless, the lives and work of both artists and curators depend on various individual factors and circumstances: the economic situation, which affects the decision to work in the arts and to what extent; a person’s social and family situation, which involves the social and familial support and understanding that should match the values of the creator; and values and beliefs, which are in turn determined by the person’s way of life, culture and social environment. All these factors directly affect the quality of life one can expect in this career. I consider myself fortunate to possess the economic and social freedom to pursue this unconventional career path, one that resonates deeply with my personal values and convictions. This freedom has enabled me to channel my creativity and skills into producing meaningful work that fills me with a sense of pride. Through my work, I’ve had the privilege to empower others and disseminate the opportunities and insights of contemporary art to diverse communities. Despite prevailing constraints on our freedom to express social and political viewpoints, I’ve found these limitations only fuel my resolve to scrutinise, challenge and critique societal norms and structures.

Me :: Community Art and Decentralisation through Alternative Art

Decentralisation is the process of sharing and dispersing power and control among local or smaller units. In the long term, this ensures that decision-making power is not confined to those at the top. The goal of decentralisation is to reduce inequality and mitigate the concentration of power. Local and marginal communities would then be able to participate in the decisions that also affect their own lives. Contemporary art practices and decentralisation are connected as contemporary art often presents socio-political views and portrays different communities’ relationships to power. This decentralisation through art can take various forms:

- Creating a space for expression of opinions which wouldn’t be possible in a more formal setting. Contemporary art practices can offer many alternative ways to have one’s voice heard.

- Listening to voices from the communities which may not have a say in the big decisions of the country. Contemporary art can help these communities get their voices heard, fostering a better understanding of their perspectives.

- Inviting responses from the larger society regarding different social and political events. Decentralisation, therefore, can have an impact on society.

- Encouraging more decisions to be made which are not determined by just one particular group of people with a specific set of values, but by a more diverse crowd where different viewpoints are considered.

The term ‘community art’ describes the creation of artistic works or activities that occur within a community or a smaller subset of society. It emphasises the involvement of the community in the artistic process through collaborative activities and practices. It promotes cooperation, relationships and connection among community members to produce artworks that hold significance for both the local community and the society as a whole. There are a variety of community art practices to suit the unique needs and dynamics of each community. These include community art in public spaces, which serves to decorate the space and connect with the community; participatory community art, wherein community members collaborate in the creation of artwork or poetry composition; problem-solving community art, designed to enhance the wellbeing and quality of life within a community through artistic works, processes or practices; and community art that focuses on the preservation of traditions and culture, with artists who are passionate about the local identity and can convey its tradition, culture and beliefs through artistic expressions.

Overall, these various forms of community art can serve as tools for decentralising power, opportunities and knowledge. They help people in communities across the country have their voices heard, understand how to exert their rights, participate in decision-making on issues that affect them, make demands and negotiate solutions to their problem, and alleviate social inequality. By fostering creative engagement within public spaces, community art serves as a catalyst for embracing local identity in each community, empowering its creative individuals to refine their talents and enhance their livelihoods. By utilising shared artistic spaces for self-expression, a dynamic exchange of traditions, cultures and beliefs transpires among communities through artistic activities that transcend the confines of traditional gallery settings.

Womanifesto & Me :: The Solution for Alternative Art

The most challenging aspect of artistic creation is the quest to establish a sustainable livelihood as a creative individual in one’s own way. It could be said that the key to a successful alternative art career lies in each person’s ability to respond to, cope with, and adapt to changing circumstances. One constantly needs to challenge oneself both in terms of creativity and skills in order to create works that are unique and interesting. This uniqueness is crucial in the survival of alternative art. One needs an individuality that doesn’t bend to market pressures or socially accepted standards or traditions. The ability to be unique and interesting in one’s work is an important part of what sustains alternative art. New spaces must be created, and new partnerships formed between creators and other stakeholders. It is also essential to thoroughly study the chosen topic in concrete ways and then collaborate with the relevant community to determine the best presentation of the works. The audience should also be allowed to engage intimately with the works, for example, through interactions with them or through a common story. Plus, the curator should play a role in assisting individual artists in their decision-making during the creative process, so that the artists can learn and expand their unique abilities. And finally, it is the curator’s job to place the work in an exhibition or present it to the media, thereby drawing global attention to alternative art.

As Womanifesto and I cross paths once more, it has been a wonderful opportunity to reflect on my work as an independent curator over the past decade. Writing this article has reaffirmed that the decision I made back then set me on a meaningful journey, allowing me to discover the true value of my curatorial work.

‘Deprived of meaningful work, men and women lose their reason for existence; they go stark, raving mad.’

~Fyodor Dostoevsky

Penwadee Nophaket Manont

Independent Curator

Founder of Rai.D Collective

Co-founder of Project-PRY

1 Womanifesto, 'Sanja Iveković'. https://www.womanifesto.com/artists/sanja-ivekovic/ (viewed March 2025).

2 King Prajadhipok’s Institute website, https://wiki.kpi.ac.th/index.php?title=Shutdownกรุงเทพฯ,

(viewed March 2025).

3 Ibid.

4 Pheu Thai Party, https://www.ptp.or.th/archives/18221, (viewed March 2025).

5 King Prajadhipok’s Institute, https://wiki.kpi.ac.th/index.php?title=รัฐประหาร2557(คสช.), (viewed March 2025).

Penwadee Nophaket Manont is an independent curator based in Bangkok. She is the founder of Rai.D Collective and co-founder of Project-PRY.

Pojanut Suthipinittharm is a translator and lecturer at Silpakron University.

Related pages

Share a Reflection

log in to share a reflection.