By Yvonne Low

Please note that this publication is currently under review and will be subject to changes.

Ten years ago, I encountered Womanifesto in the writings of Varsha Nair and Phaptawan Suwannakudt. Little was I to know that in 2015, when I briefly highlighted Womanifesto’s activities in a short essay surveying women-centred exhibitions and projects in Southeast Asia, my own personal and professional trajectory would later, serendipitously intersect with Womanifesto’s feminist history—and that I would form such endearing, life-changing friendship with key members along the way as well. In a creative essay for Womanifesto’s retrospective exhibition in 2023, jointly written with Roger Nelson, I reflected on these friendships and dwelled on the challenges of being a working mother in academia as I struggled to find a place in the wider field and my new country of residence, Australia. I went on to recognise the struggles and career aspirations of other Womanifesto artists and this recognition grew out from my friendship with them, as I engaged with the stories of their professional and personal lives; increasingly, I see that this story about the friendship between women artists throughout Womanifesto’s history is about ‘us’, as much as it is about others.

An Introduction: What is the Role and Function of an Archive?

In 2020, Asia Art Archive (AAA) launched the Womanifesto Archive, an online archive project that was supported by AAA Women and Gender Diversity Fund, and completed in collaboration between the founders and members of Womanifesto, and the archivists and researchers at AAA. The archive is a whopping 734 online records that are systematically organised across sixty-eight folders and divided into eight sections: Administrative Papers and Correspondence, Photographic Documentation, Audiovisual Documentation, Press Clippings and Articles, Publications, Ephemera, Artworks and Objects, and lastly, Archiving Womanifesto Exhibition. AAA represents one of the few independent non-profit institutions in the region to emerge from a postcolonial position and actively address Western institutional hegemony. Chantal Wong and Janet Chan, writing for Asia Art Archive, have proclaimed the ‘archive’ to be a ‘method’, a means to ‘counter, complicate, and reimagine systems in which narratives of modern and contemporary art are being produced, circulated, and understood’.1 AAA's decision to include Womanifesto, Southeast Asia's first transnational feminist and women-centred art collective, in its collection clearly reflects this methodological impetus to facilitate the re-writing of canonical narratives that had systemically excluded women's contributions.

AAA’s digitisation of the Womanifesto Archive and its accessibility on the AAA website are further underpinned by the organisation’s self-reflexive approach which serves to in the words of Chan and Wong, ‘collate and enable access to documentation and networks of knowledge that are alternative to existing universalist epistemologies’.2 After all, to ‘archive’, as Paul Clarke reminds us, is fundamentally ‘to give place, order and future to the remainder; to consider things, including documents, as reiterations to be acted upon; as potential evidence for histories yet to be completed’.3 This active collecting of so-called ‘potential evidence’ in fact started a good two decades prior when the idea of putting together an archive was discussed by Varsha Nair and Nitaya Ueareewarakul, the organisers of a Womanifesto event in 1999 that eventually saw the amassing of the documentation digitised on AAA. Theirs was a decision underpinned by a feminist position that aims to combat the forgetting of women’s work in the art world. Questions such as what constitutes an archive, and how archives have engendered realities, if not shaped as opposed to merely preserving realities, have emerged in recent scholarship.4 Significantly, feminist perspectives have highlighted the urgency to consider the role of archives in feminist knowledge making—as Maryanne Dever explains to ‘actively problematise what an archive is and what an archive does’.5 Scholars have shown that archives are alive and constituted not only through the works they contain but through ‘networks of community memory and community activity’.6 To this end, archiving as an ‘active verb’ has the potential to also ‘produce collectives, or models for future collectivity’.7

In this regard, the Womanifesto Archive co-produced by Varsha Nair, Nitaya Ueareewarakul and Phaptawan Suwannakudt—the very artists themselves—offers immense potential for real intervention to take place, operating as a site of feminist connectivity. From press releases to sketches and notes to email correspondences, the archive foregrounds the resilience of feminist labour— it shows irrefutable evidence of a lifetime of ‘maintenance’ work by artist-organisers. Filipino scholar Eileen Legaspi-Ramirez made the trenchant observation that maintenance tasks often disproportionately befall women cultural practitioners, in an essay that sought to question the wider, flawed enterprise of art history as comprising always bias and subjective narratives.8 There are no objective truths, only agendas and differing perspectives—as I have often shared with my students in courses on Writing for the Art and Museum Sector, and in Gender and Sexuality in Asian Art History at the University of Sydney. Then and elsewhere, I have quoted Flaudette May Datuin who had quoted Griselda Pollock, that it is a fallacy to assume that the art historian is a mere vassal for the artwork and the artist’s ideas, as if there is only one set of truths.9 The re-telling process is always a mediated one.

Returning to Womanifesto Archive, I do not see it as harbouring a set or even multiple sets of truths; instead it harbours the manifold potentiality to tell, here used as an active verb. But who is telling? In early drafts, I clarified my position as not merely reiterating histories, or offering compensatory histories to bring to the fore women’s visibility, for both Varsha and Nitaya have done so for themselves (and perhaps other women) through textual and visual accounts. Mine was an ambiguous position because I maintained sole authorship that aimed nonetheless to disavow the patriarchal position of speaking for them by speaking with and alongside them. Yet, it is precisely in our desire to tell (first to each other, then to others) that we become agents of change, fully cognisant of the feminist labour involved in reclaiming stories and reconfiguring power dynamics. Here it may be generative to take up feminist historian Antoniette Burton’s call to recognise the ‘indeterminance’ in efforts of archive-making—where an archive of women’s memory serves as neither a primary or a secondary source because it ‘participates in and helps to create several levels of interpretative possibility’.10 Thus, as we recognise the fundamental liminality of the archive, and revel in the possibilities that an archive such as this might offer to the future researcher, we also recognise and acknowledge the valiant effort of these women who, like others before them, have tried to ‘preserve themselves as remembering subjects’.11 The following investigation into memory-making and the making of a feminist archive is rightfully also co-produced with Varsha and Nitaya, and the aim here is to foreground their role and lifetime’s work in fostering feminist connectivity.

Acts of Remembering: Writing, Talking, Cutting, Pasting …

Archive-making as approached by Varsha and Nitaya has always been intimately built on and facilitated by feelings of amity where the labour of documenting is not merely to remember past events that they are evidently fond of, but also a means in which they could preserve themselves as remembering subjects. The story of how Varsha and Nitaya met and became the key organisers of Womanifesto might be described as serendipitous, when Varsha moved temporarily to Bangkok from India in 1996 and as an expatriate was actively seeking out the local artistic community. Then, Nitaya was running her own art space, Studio Xang, which she had established with her partner. Studio Xang was described by David Johnson to have ‘a very co-operative like feel’ and as a place where ‘uncompromising and socially driven art works could be viewed’.12 Nitaya, who was faced with the challenges of fundraising and organising Womanifesto I, in 1996, welcomed the contribution from Varsha.

The exhibition, which saw the participation of eighteen artists from nine countries, took place on World Women’s Day in March 1997, a time of the year that worked particularly well for women, as explained in the catalogue essay:

Their schedules are not very busy as it is the final term break for school children; the end of the harvest season for rice growers; teachers have their days of rest and laborers as well as civil servants like to take their holidays at this time.13

Touted to be the ‘first of its kind in Asia’, the exhibition had stated aims and objectives that were carefully couched in feminist terms: to re-define artistic autonomy and expression from women’s perspectives whilst affirming the unique oppression of women as universal. In this early exhibition there was already a marked differentiation from institutionally conceived events where artists were formally selected or invited; here the artists came together ‘via personal connections and friendship’.14 This model continued for subsequent exhibitions, with artists tapping into personal networks to recommend other artists and artists self-nominating themselves as organisers for future projects.15

In the Womanifesto Archive, the textual documentation (essays and speeches) and visual documentation (albums) created by Varsha and Nitaya, respectively, serve as embodiments of their subjective gaze in their individual storytelling. Unlike other collectives in the region, such as Chiang Mai Social Installation, the history of Womanifesto—at least of how it began, what activities it supported and who was involved in it—was given unequivocal authorial clarity from early on. Not only was its history consecrated in the writings of key Womanifesto members, there was also unanimous support from all the participants of its second exhibition in 1999 for the establishment of an archive of women’s art.16

Since then, Varsha and Nitaya have amassed a deep and rich record of all Womanifesto-related events that comprises photographic documentation, audio-visual documentation, press clippings, correspondence between artists and organisers and sponsors, speeches and all event-related collateral. This approach to record-keeping stands in contra-distinction to the challenges that David Teh was reflecting on when conducting research in Thai culture and history, where Thai people’s aversion to material documentation revealed to Teh that Thais were often ‘inclined to elaborate, filter or forget the past, not to record or study it’, not because the artists were ‘cash-poor’ and living ‘non-archival lives’ but because it was an ‘episteme’.17 Trinh T. Minh-Ha reminds us of the triple bind where women in such contexts were frequently doubly othered, and where Southeast Asian scholars are faced with the challenge of making their voices heard in the first place.18 Teh was perhaps aware then that an ‘un-Thai’ approach was well underway, for the opposite was surely observed in the systematic and meticulous approach both Varsha and Nitaya had taken upon themselves to ‘make visible what [they] were doing and thus connect it with the wider discourse going on out there’.19

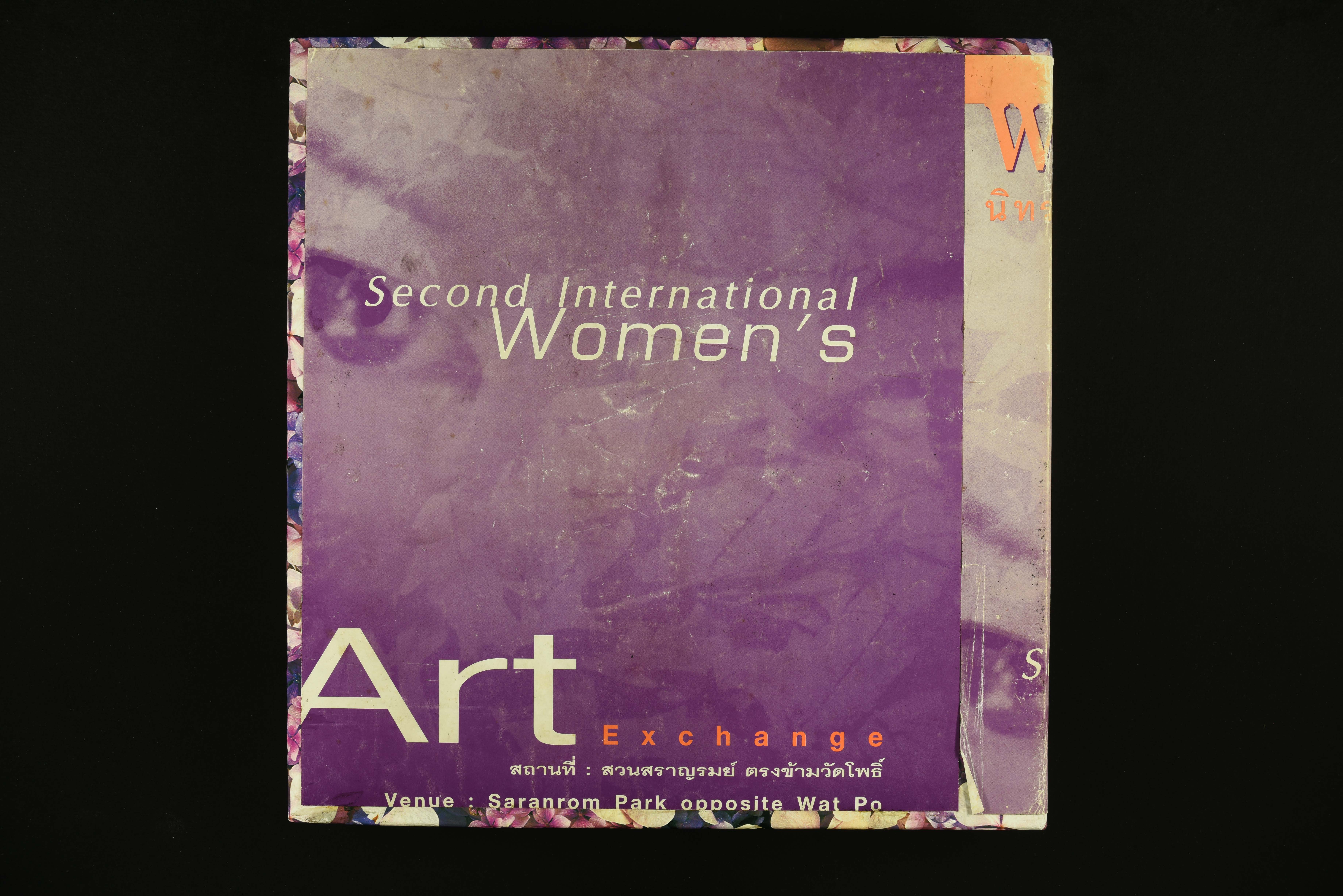

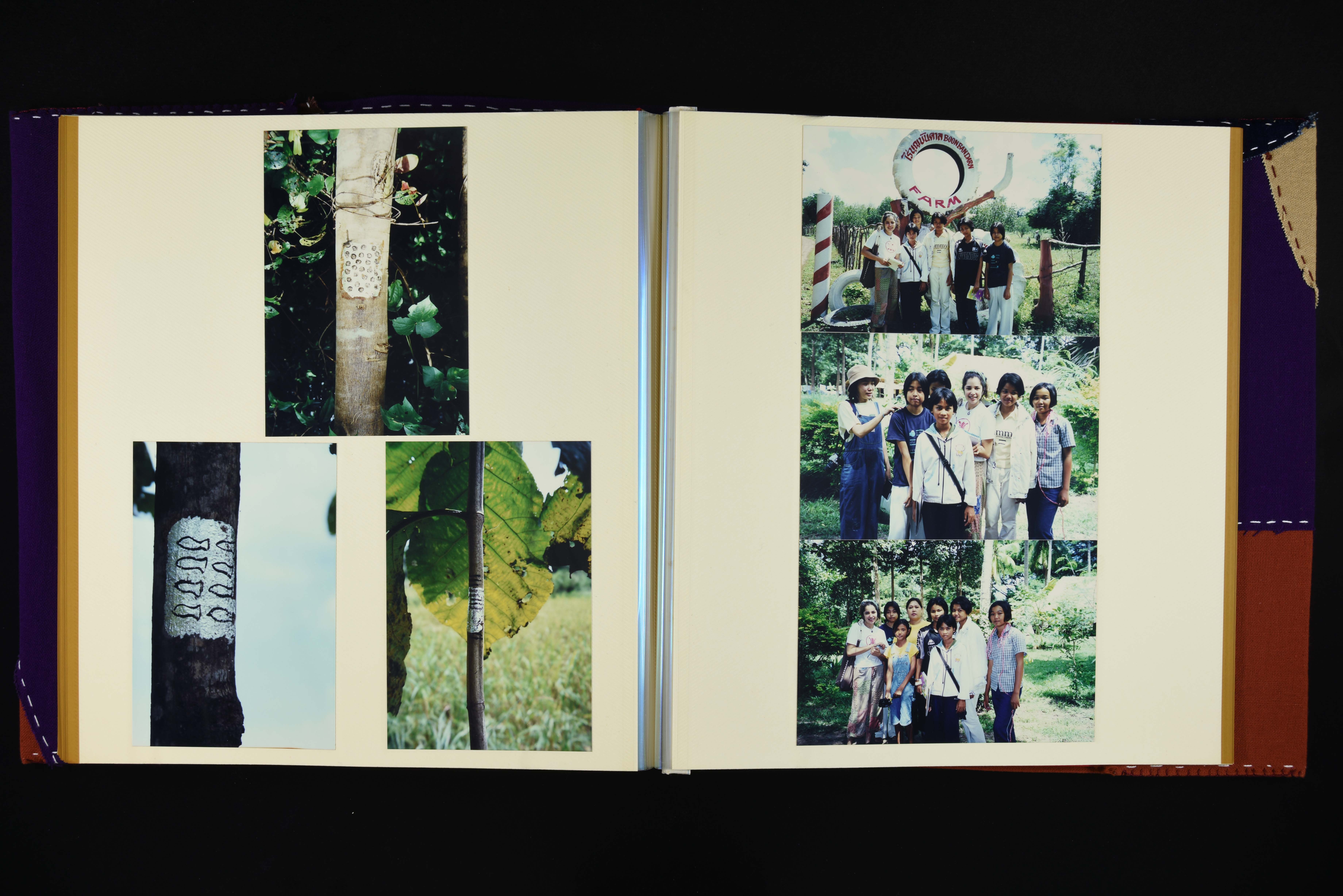

One of the first steps to building the archive was to compile and collate photographic documentation of the 1999 event which was subsequently reconfigured into a visual album. Nitaya refurbished the cover of a store-bought sticky-back photo album with official Womanifesto collateral: a flyer that they had printed to publicise the event. The entire album took on an appearance of a well-loved scrapbook that could at first glance have been dismissed as a high-school project. Text was typed out using a word processor in Thai and English, then printed on white paper, before it was cut and pasted or inserted into the album pages alongside the photographs of the works and events. The album follows a loose chronology of events beginning with the reception of the artists at Saranrom Park, the works themselves, and snippets of the official program that included the opening of the event, the conference and other social events. This ‘album’, as Nitaya calls it, served multiple objectives beyond record-keeping: in a time before the widespread use of tablets and laptops, the album, which could be carried around with relative ease, offered a crucial visual record to authenticate the past work of women artists for potential sponsors.20

In the years following, Nitaya went on to create four similar albums, albeit for different purposes. They all nonetheless revealed an explicit conceptualisation of the archives in the manner of a photo album. Serving as a textual narration to these albums are Varsha’s many writings and speeches which further illuminated the multiple, and often informal, roles that they and their Womanifesto collaborators took on: as organisers, administrators, archivists, fundraisers, publicists, photographers, advocates and others. Varsha demonstrated an acute awareness of not only feminist discourse, but existing platforms among which to contextualise the significance of such women-centred events and exhibitions in a male-dominated art world context. ‘Writing’ and ‘presenting talks’ have been identified as two key strategies by Varsha in which to give authority and legitimation to women’s work.21 The objectives of Womanifesto were outlined in carefully worded prose, its rhetoric echoing the core principles of second- and third-wave feminism, with assertions for giving women equal access in society whilst recognising race and gender differences:

To promote a greater awareness of women in the society in which they exist by presenting their ways of thinking and doing things, which will ultimately effect [sic] among other things, the conservation of our environment as a whole. To stimulate a wider appreciation of creative ways of thinking towards our world society and the use of intellectual activities and all disciplines of art as forms of free expression. To help create the right atmosphere for a lively forum among Thai and international women artists where exchange of experiences can flow freely, regardless of different cultural roots.22

Furthermore, in Varsha’s eloquent description of the events, her writings served to re-enact the many moments of exchange captured in the photographs, giving these context and meaning. In this regard, serendipitously, Varsha and Nitaya have filled the gaps for each other in the archive-making process. By visually and textually recording their histories of Womanifesto, respectively, both Nitaya and Varsha have demonstrated their resilience and creativity in making such added professional responsibilities work for their practice and their professional growth as contemporary artists.

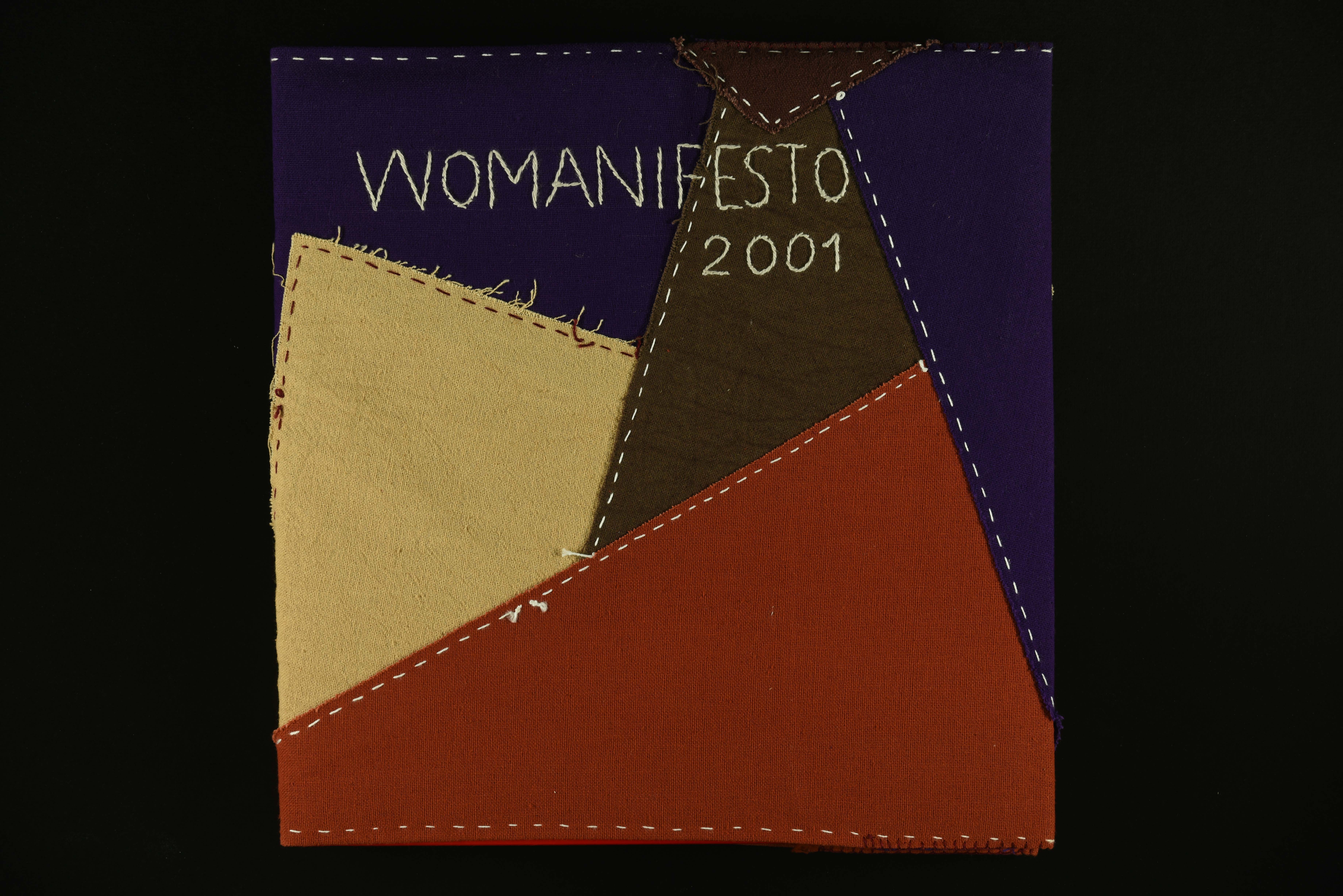

To this end, it is the friendship and camaraderie the two women artists shared that has played no small part in supporting their Womanifesto ‘maintenance’ work, and in subsequently sustaining their feminist efforts. Speaking for the importance for women especially to intervene in the history of art, of culture, of institutions and of consciousness, feminist art historian Linda Nochlin believed in the active engagement and participation of viewers and readers of art and art history.23 The albums that Nitaya created were far from mere placeholders of photographic documentation. Being active viewers and readers means to see beyond the album’s quotidian or instrumental function to consider how it can also perform an ‘enabling’ function—for instance, it has become the medium for Nitaya to remember, in a similar way to how the frame could serve in the words of May Adadol Ingawanji ‘the condition of possibility that lets the painting be the painting that it is’.24 Whilst the first album may have served a more practical function in the form of a kind of portfolio of sorts to elicit support from future sponsors, the second album, which was completed after the 2001 Womanifesto Workshop, demonstrated a more personal and subjective approach. This time, the cover was not constructed out of an artefact that spoke of a past; it was meticulously hand-sewn using pieces of woven fabric with the name ‘Womanifesto’ and the year ‘2001’ embroidered neatly across the front.

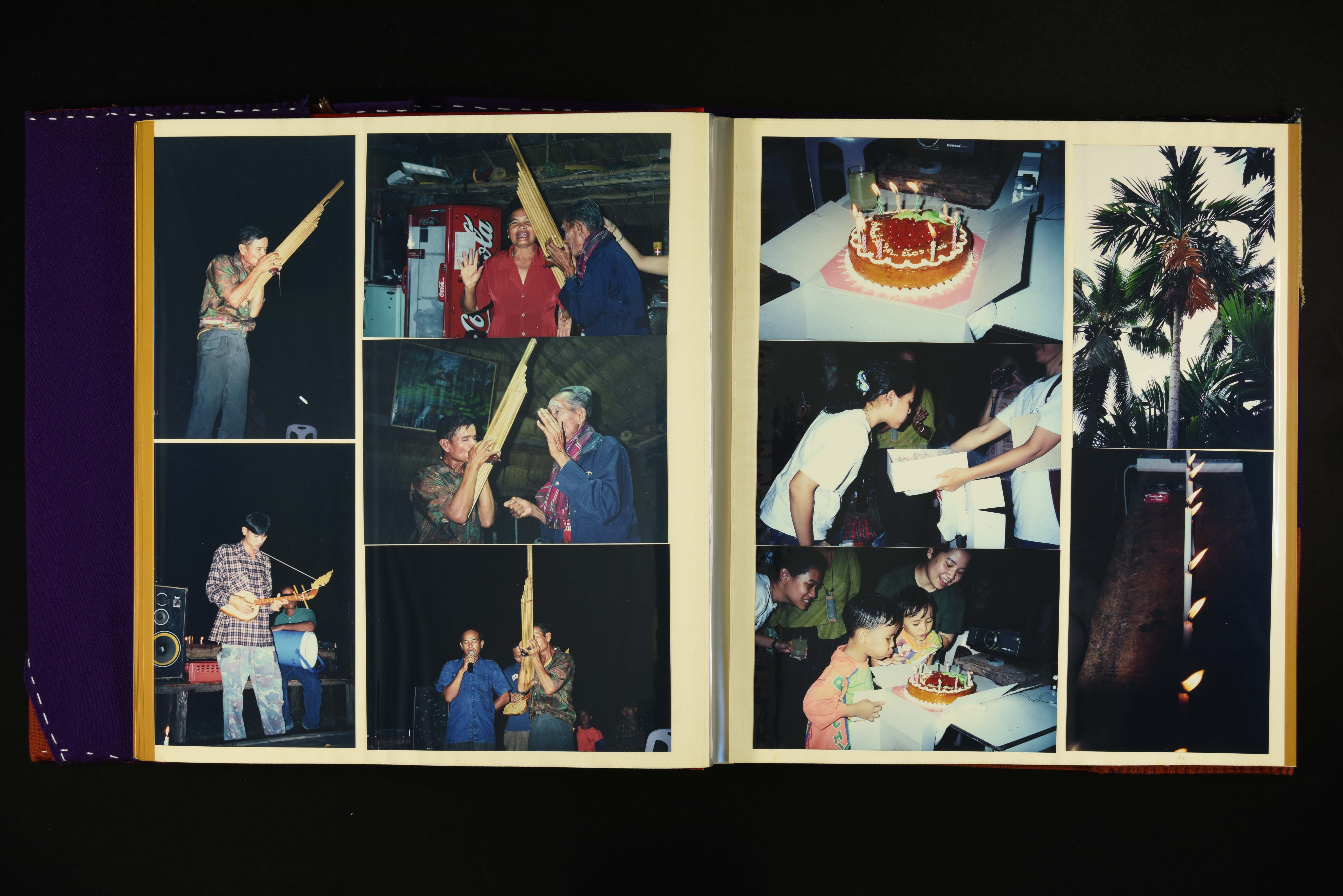

Another distinct difference in the second album is how the photographic documentation was laid out across the pages, very much in the manner of a conventional photo album and devoid of any type-writing or captioning. This is a marked departure from the many textual descriptions pasted throughout the first album alongside the photographs that recalled the form and format of an exhibition catalogue: titles, captions, artist’s statements, and event details. When asked why that was the case, Nitaya explained that there were ‘too many interesting photos’ and so she filled the page up and let the ‘photos [tell] the stories’.25 The selection and arrangement of the photographs evokes a strong whimsical and nostalgic sentiment, with snapshot after snapshot depicting the rustic charm of the Si Saket region in north-eastern Thailand, where the workshop was held. The pages unveil tranquil scenes of the Boon Bandarn farm that were momentarily interrupted by the arrival of jubilant and excited visitors.

For ten days, eighteen professional women from across the world and five Thai student volunteers made the mud huts on the farm their temporary home as they engaged with the local crafts people and community and explored local materials and a traditional way of life.26

Designed to ‘initiate dialogue and create a dynamic environment for process and exchange’, the workshop’s objective was not for the participants to show their final work but for them to freely ‘devote the time to gather material and document to use at a later date’.27 Where the first album may have focused on the artwork itself, with each artist represented by a photograph or several photographs of her exhibited or performed piece, in the second album the focus was less on art work per se than on the creative processes that might enable it, with the vast majority of the photographs showing glimpses of the event-filled program that occupied the participants throughout the workshop.

Nitaya had in fact started on the album immediately after the 2001 event, but was not able to complete it until 2019 when Womanifesto curated a travelling exhibition on their archive, shown first in Bangkok at Chulalongkorn University, and then in Sydney at The Cross Arts Projects. Conceived out of the Gender in Southeast Asian Art Histories conference that was organised by a group of feminist art historians based in Singapore, Sydney and Bangkok, Nitaya and Varsha (with assistance from others) decided to create three more albums for this inaugural exhibition. The aim was to enable the archive to be viewed with ease and to encourage viewers to touch, hold and flip through the albums—not very different from how one would share an album of photos with friends and family in one’s home.28 This conviviality and hospitality was central to the ethos of Womanifesto—vividly captured in the photographs showing members’ homes or meals shared with one another. Reminiscing as it turned out was a shared pleasure between the co-curators and other members involved in the exhibition that more than made up for the challenges and physical demands—sorting, hanging, packing and unpacking—of putting up the exhibitions. Varsha wrote of the experience shortly after:

Unpacking the boxes and going through the stored documents/material and preparing to exhibit the Womanifesto archive we found ourselves going down memory lane, somewhat overwhelmed with the diversity of projects, artistic expressions […] The documents, photographs/slides/negatives, letters, drawings that passed between our hands became living, breathing things—palpable memories which we were now reconnecting with, and thus reliving.29

Here the explicit reconfiguration of the viewing process of an archive into a regular photo album serves to take one on a trip down memory lane. As the photos tell manifold tales depending on the viewer’s relationship with the subject depicted, they crucially also speak to a history through Nitaya’s subjective gaze embodied in the process of making these albums: selecting, pasting and organising. To this end, the albums themselves function as a medium that has enabled her recollection of the past, making visible her subjective gaze.

In the process of making the archive, Nitaya’s mode of retelling the event has been concomitantly historicised. This suggests that what was included in the album was more revealing of what Nitaya thought was important to remember than of what might be revealed in the photograph itself. The photographs, for example, of a quietly swaying betel nut tree that formed so much of the backdrop of the rural community, or the surprise birthday celebration thrown for Nataya Masawisut, one of the volunteers, whilst forgettable and seemingly ‘insignificant’ in canonical narratives of art, were evidently not so to Nitaya.30 They represented memories that she wanted to keep. Whilst Nitaya has not necessarily conceived of her albums as addressing sexual politics per se, it is nonetheless possible to consider their contribution to a feminist objective by taking into account their subjectivity—a woman’s subjectivity—in the production process.

In this regard the albums are evidently examples of highly contextualised publications that serve a feminist end in positing the authority of one woman’s taste or gaze. In Elizabeth Grosz’s compelling study on the materiality of texts and the subjects of writing and reading practices, she cautions: ‘The text’s materiality exerts a resistance, a viscosity, not only to the intentions of the author but also the readings and uses to which it can be put by readers.’31 Her study problematises the notion of ‘intention’ and demonstrates how the relations between text and author/readers is far more enfolded and mutually implicating. Grosz reminds us that the author’s corporeality is an always sexually specific corporeality. Nitaya’s presence as a female corporeality is evoked in the traces of her handiwork: the hand-sewn fabric cover of the albums which used leftover pieces of cotton fabric.

Each album took several days to complete; these covers are elegant works of art in themselves that speak directly to Nitaya’s lifelong engagement with materiality in her art practice. Whilst Nitaya has always been drawn to the use of common-place objects (paper, plastic bags, rope) in her practice, since moving to Ubonratchathani in 2012, she has been designing and hand-sewing clothes and apparel using local materials. As she reflected when she became a single parent to her children, it was a period that entailed ‘working a lot’ with her two hands—a finessing of a craft that was also deeply meditative and seemed a possibly healing and cathartic process.32 These fabric covers functioned as more than mere protection for the album: inasmuch as they serve to aestheticise the album and subjectivise the viewing process, these covers also enable Nitaya to partake in a storytelling process, giving her time and her art and handiwork to the album viewer, whoever it may be. Here, examining the ways in which the sexuality and corporeality of what is here the maker’s handiwork leave traces or marks on the texts produced can enable seeing more clearly how the question of sexual specificity (sexuality) is relevant to the question of textuality that in turn can serve feminist ends. Nitaya's personalisation of seemingly ‘official’ collateral connects to a broader history of women documenting their lives through scrapbooks and memoirs, functioning simultaneously as both performance and archive.33

Reflections: Friendship and Feminist Connectivity

As I write about Varsha’s and Nitaya’s roles as producers and engenderers of the Womanifesto archive, I reflect as well on my friendship with them that has been built and fostered through collaborative work on women’s practice in art history—here, with the aim to develop a methodology that may enable a more autonomous retelling of alternative histories. Friendship as a central topic does not figure prominently in the discipline of art history, with social relations often explored in terms of a larger artistic ecology or network of influence, for example art associations, ateliers and patronage circles.34 Recent studies have illuminated the politics of friendship in the context of exhibition-making during the Cold War period,35 and in the study of artist-residency formats in contemporary Indonesia.36 In a reflective piece of writing for AAA’s e-journal, Field Notes, Vietnam-based curator Zoe Butt discussed the significance of friendship in her field, defined here as ‘the ideologically monitored, commercially hoodwinked terrain of China and Vietnam’. In clear terms, Butt states: ‘I came to understand just how significant friendship is to sustaining the development of artistic languages and forms—and how it can provide political autonomy with a powerful organised presence.’37 These human-to-human connections, including those between friends, remain under-theorised, looming in more casual conversation and left out of official art histories. Yet, friendship is central to the founding of Womanifesto and the making of its archive; it is in fact the very subject pictured, captured and archived.

Not only have such informal networks of friendship been a key contributing factor to the successful development and organisation of Womanifesto projects, the friendship between the women artists crucially also helped them to navigate the myriad challenges encountered throughout their professional journey. Reflecting on the history of Womanifesto, Varsha’s writings were often semi-biographical as she ruminated on her artistic career, and the friends and life choices that she had made. Her remark, ‘[t]hus begun our friendship and my long engagement with Womanifesto’, was qualified with an introspective consideration of how this engagement had become meaningful in defining her own journey, impacting the decision to settle down to live in Thailand, and how she had come into her own as an artist.38 This admission is also a tacit acknowledgement of the impact Womanifesto and the relationships formed might have had on her own professional practice and where they might have given her purpose and meaning in life.

Trained in the fine arts with a major in painting at the renowned Maharaja Sayaji Rao University in Baroda, Varsha has developed a practice that is conceptually grounded and multimodal/disciplinary in its execution. From her recollection, although plans to further study in the UK where her family had moved did not materialise, the decade spent in the UK from 1980 was evidently formative, for it gave her the opportunity to pursue professional cultural work at a design centre in London that ultimately equipped her with organisational skills.39 Coincidentally, these skills complemented Nitaya's resourceful and entrepreneurial abilities. Through running Studio Xang, Nitaya had created a professional networking platform that promoted Womanifesto-related activities during the early period.40 Nitaya envisaged Studio Xang as an art space that would introduce more liberal art practices to Thai youth, while offering art classes to children would provide financial sustainability.41 As a fine arts graduate of Chulalongkorn University, Nitaya was among the steadily growing cohort of Thai female artists eking out a professional career as a contemporary artist which entailed running an art space, teaching art and organising events; within a ten-year period from 1990, she had achieved five solo exhibitions, producing a prolific body of work that spans paintings and multi-disciplinary works.

Much of Nitaya’s practice drew from her own life experiences, including her reflections on Buddhist philosophy and the everyday pressures she felt performing multiple roles. Fuelling her organisational work for Womanifesto was a belief in the strong injustice in the treatment of women in Thai society, of ‘the subservient and inferior role they have to take below men’.42 Whilst her practice has grown to perform a more personal and cathartic function, where the reason for painting ‘is to see [herself]’ and to ‘see’ what she is ‘thinking’, her aspirations for Womanifesto served clear feminist aims to correct a gender imbalance.43 And to achieve this meant that women-centred platforms were necessary to encourage ‘greater interaction among young Thai female artists’, who she felt were still reluctant to make their voices heard.44 This seemed all the more pertinent for introverted personalities keeping in mind that this insightful remark was itself made by a self-professed ‘loner’, someone ‘very introspective’ and ‘not too sure of [herself]’.45 When interviewed by arts writer Steven Pettifor, she tellingly described Womanifesto as being ‘about building friendships with females from other countries’ and an ‘exciting opportunity for communicating through collaborative activities’.46

Crucially, it is the autonomy to practice—what Womanifesto most fundamentally offered to women artists—that was to have the most significant impact on Varsha. When describing Womanifesto as ‘an exciting playground’, Varsha revealed a deep reflection into the contemporary constraints of the art market and the increasing institutionalisation that was reshaping art practice.47 Eleven years after her relocation to Bangkok, Varsha observed the ‘vibrancy and creative energy’ that was so important in artist-led platforms dissolve against the rise and control of an art infrastructure that emerged and manifested in cities and elsewhere across the world.48

These challenges were further exacerbated by gender-based obstacles. Where women artists were disadvantaged as a result of patriarchal conditions, a woman-centred platform such as Womanifesto aimed precisely to offer a professional and convivial space for women to gather and exchange.49 ‘Gathering’ as a verb denotes the coming together of individuals; it has since been borrowed from philosophy, describing man’s pre-social relation to the earth, to convey a race-based and/or feminist-derived position of empowerment.50 Women’s gathering has been observed by feminist historians to have enabled women to come to terms with the nature of their oppression. As Gerda Lerner has shown, sex-segregated social space became the terrain in which ‘women could confirm their own ideas and test them against the knowledge and experience of other women’, and in so doing help ‘women to advance from a simple analysis of their condition to the level of theory formation’.51

Varsha and Nitaya have quietly engineered a model of self-sustainability, drawing on their friendship for support, to overcome the double-marginalisation that women as artists have experienced and continue to experience in a male-dominated, patriarchal system. The documentation of Womanifesto events and the making of its archive, however laborious it is as ‘work’, is also a process that is built on and facilitated by such feelings of amity. Whilst Nitaya and Varsha had welcomed the institutional support from AAA to digitise their archive, they are not lulled by the fantasy of ‘digital permanence’.52 Reflecting on their exhibitions of the archive, Varsha wrote of the importance of maintaining their ‘analog connections’ as plans for establishing a centre for Womanifesto on Nitaya’s land outside Udon Thani were already underway:

This would be a physical space where the original archive materials will be exhibited, and a connected studio space which will host artists as residents. It is an exciting development, this room of one[’]s own, which we aim to settle down in [sic] starting in March 2020.53

However, this step toward creating a physical archive space does not represent naive faith in permanence. As Varsha had spoken frankly about the realities of loss—digital files erased, artworks eaten by termites—their approach remains grounded in an understanding of archives’ inherent vulnerability.54 As this brief account of the archive’s making has shown, what the archive has offered for Nitaya and Varsha is a means to reproduce alternative histories rooted in women’s own experiences and truths. The archive, as Karen Steele reminds us, beyond making things official or institutionalised, is itself gendered and predicated on social norms.55 Nowhere is this more viscerally observed than in Nitaya’s hand-made albums of photographic documentation or Varsha’s written essays and delivered speeches that sought to overcome a long history of exclusion of women’s voices or other forms of feminine guides (namely memoirs, letters, scrapbooks) in traditional archives. Significantly, as producers and engenderers of the Womanifesto archive, Nitaya and Varsha have given themselves and other women a space of their own in which to dwell, to gather.

Notes

1 Chantal Wong and Janet Chan, 'The Archive as Method', Field Notes, no. 2, pp. 3–10. Also republished in Like a Fever, December 2012. HYPERLINK "https://aaa.org.hk/en/ideas/ideas/archive-as-method/type/essays"https://aaa.org.hk/en/ideas/ideas/archive-as-method/type/essays ,accessed December 2021.

2 ibid., p.5.

3 Paul Clarke et al., ‘Introduction: Inside and Outside the Archive’, in Paul Clarke et al. (eds), Artists in the Archive: Creative and Curatorial Engagements with Documents of Art and Performance, Routledge, London, 2018, p. 11.

4 See Ann Laura Stoler, 'Colonial Archives and the Arts of Governance', Archival Science, vol. 2, 2002, pp. 87–109; Ann Laura Stoler, Along the Archival Grain, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2009; and Marain Pastor Roces, 'Archive', Ctrl+P, no. 19, 2019, pp. 6–10.

5 Maryanne Dever, 'Archives and New Modes of Feminist Research', Australian Feminist Studies, vol. 32, no. 91–2, 2017, p. 2.

6 See Lewis Kaye, 'Reanimating Audio Art: The Archive as Network and Community', else arts + opinions, no. 78, 2013, pp. 68–71; and Jeannette Bastian and Andrew Flinn, Community Archives, Community Spaces: Heritage, Memory and Identity, Facet, London, 2020.

7 Catriona Moore, 'Coming Together: Collective Actions and Future Feminist Archives', public program presented as part of the exhibition Archiving Womanifesto: An International Art Exchange, 1990s–Present, The Cross Art Projects, Sydney, December 2019. Also see ‘Archiving Womanifesto: An International Art Exchange, 1990s – Present’, The Cross Art Projects, https://www.crossart.com.au/exhibition-archive/114-2019-exhibitions-projects/355-archiving-womanifesto-an-international-art-exchange-1990s-present ,accessed December 2021.

8 Eileen Legaspi-Ramirez, 'Art on the Back Burner', Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia, vol. 3, no. 1, 2019, pp. 25–6.

9 Flaudette May V. Datuin, Home Body Memory: Filipina artists in the visual arts, 19th century to the present , University of the Philippines Press, Diliman, Quezon City, 2002, p. 33.

10 Antoinette Burton, Dwelling in the Archive: Women Writing House, Home, And History in Late Colonial India, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2003, p. 23.

11 ibid.

12 David Johnson, 'Face to Face', Expression, 1997, pp. 44–46.

13 'Background', Womanifesto: An International Women’s Art Exchange Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, Concrete House, and Baan Chao Phraya, Bangkok, 1997, unpaginated. The opening took place at Concrete House and Baan Chao Phraya on Saturday March 1 1997. The exhibition was held from March 2-31, 1997

14 Sompom Rodboon, ‘Voices of Womanifesto’ in Womanifesto: An International Women’s Art Exchange Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, Concrete House, and Baan Chao Phraya, Bangkok, 1997, unpaginated.

15 See Varsha Nair, 'Womanifesto: A Biennial Art Exchange in Thailand', Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia, vol. 3, no. 1, 2019, pp. 147–73.

16 Varsha Nair, 'Womanifesto—jogging ahead', n.Paradoxa, vol. 4, 1999, pp. 91–94. Also republished here.

17 David Teh, 'Artist-to-Artist: Chiang Mai Social Installation in Historical Perspective', in Artist-to-Artist: Independent Art Festivals in Chiang Mai 1992–98, Afterall, London, 2018, p. 46.

18 Trinh T. Minh-Ha, 'The Triple Bind', in Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism, Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1989, p. 6.

19 Varsha Nair, ’Amidst Fire, Gnawing Termites, and Other Factors of Erasure—Womanifesto Roots Down in the Digital World’, paper presented at Gender in Southeast Asian Art Histories II: Art, Digitally and Canon-Making, University of Sydney, October 2019.

20 Interview with Nitaya Ueareewarakul, 17 August 2021.

21 Nair, ‘Amidst Fire, Gnawing Termites, and Other Factors of Erasure’.

22 ‘Background’, Womanifesto: An International Women’s Art Exchange Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, 1997.

23 Linda Nochlin, Representing Women, Thames and Hudson, London, 1999, p. 33.

24 May Adadol Ingawanij, 'Making Line and Medium', Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia, vol. 3, no. 1, 2019, p. 18.

25 Interview with Nitaya Ueareewarakul, 17 August 2021.

26 Varsha Nair, 'Artists Retreat to Countryside', SPAFA Journal, vol. 12, no. 1, 2002, p. 31.

27 ibid.

28 Interview with Nitaya Ueareewarakul, 17 August 2021.

29 Varsha Nair, 'Archiving Womanifesto, and Much More …', Ctrl+Pdf: Journal of Contemporary Art, no. 19, 2019, p. 16.

30 Interview with Nitaya Ueareewarakul, 17 August 2021.

31 Elizabeth Grosz, 'Sexual Signatures: Feminism After the Death of the Author', in Space, Time and Perversion: Essays on the Politics of Bodies, Routledge, London, 1995, p. 17.

32 Interview with Nitaya Ueareewarakul, 17 August 2021.

33 See Ellen Gruber Garvey, Writing with Scissors: American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance, Oxford University Press, New York, 2013; and Katie Day Good, ‘From Scrapbook to Facebook: A History of Personal Media Assemblage and Archives’, New Media & Society, vol. 15, no. 4, 2012, pp. 557–73.

34 See Michelle Antoinette and Francis Maravillas, 'Positioning Contemporary Art Worlds and Art Publics in Southeast Asia', World Art, vol. 10, no. 2–3, 2020, pp. 161–89; Yvonne Low, 'Becoming Professional Artists in Postwar Singapore and Malaya: Developments in Art During a Time of Political Transition’, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, vol. 46, no. 3, 2015, pp. 463–84; and Patrick Flores and Low Sze Wee (eds), Charting Thoughts: Essays on Art in Southeast Asia, National Gallery Singapore, Singapore, 2017.

35 See Brigitta Isabella, 'The Politics of Friendship: Modern Art in Indonesia’s Cultural Diplomacy, 1950–65', in Stephen Whiteman, Sarena Abdullah, Yvonne Low and Phoebe Scott (eds), Ambitious Alignments: New Histories of Southeast Asian Art 1945–1990, Power Publications and National Gallery Singapore, Sydney and Singapore, 2018, pp. 83–106.

36 Mitha Budhyarto, 'Hospitality, Friendship and an Emancipatory Politics', Seismopolite Journal of Art and Politics, no. 13, December 29, 2015, unpaginated. http://www.seismopolite.com/hospitality-friendship-and-an-emancipatory-politics (accessed December 2021).

37 Zoe Butt, ’Practicing Friendship: Respecting Time as a Curator’, Field Notes, no. 5, p. 7. https://aaa.org.hk/en/like-a-fever/like-a-fever/practicing-friendship-respecting-time-as-a-curator, accessed December 2021.

38 Nair, ’Womanifesto: A Biennial Art Exchange in Thailand,’ p. 148.

39 Email to the author, 21 December 2021.

40 Steven Pettifor, 'A Mantra of Unity', Asian Art News, vol. 10, no. 6, 2000, pp. 89–91.

41 Steven Pettifor, 'Acrylic Impressions', The Nation, 1997.

42 ibid., n.p.

43 David Deveraux, 'The Mirror has Two Faces', METRO, 1997, p. 67.

44 Pettifor, ‘A Mantra of Unity’, p. 89.

45 Joyce Rainat, ‘A Mind of Her Own’, Bangkok Post, 2 July 1997, unpaginated.

46 Pettifor, ’Acrylic Impressions’, n.p.

47 Nair, 2019b, p. 148.

48 Varsha Nair, 'Amidst Art Platforms with Dilute Foundations, Womanifesto Roots Down and Continues to Distill', Ctrl+Pdf: Journal of Contemporary Art, no. 6, 2007, p. 8.

49 Nair, ‘Womanifesto - jogging ahead’, p. 94.

50 Sarah J. Cervenak, Black Gathering: Art, Ecology, Ungiven Life, Duke University Press, Durham, 2021, p. 5; see also Rosemary Betterton, An Intimate Distance: Women, Artists and the Body, Routledge, London, 1996.

51 Gerda Lerner, The Creation of Feminist Consciousness from the Middle Ages to Eighteen-Seventy, Oxford University Press, New York, 1993, p. 279.

52 Deborah Withers, 'Ephemeral Feminist Histories and the Politics of Transmission within Digital Culture', Women’s History Review, vol. 26, no. 5, 2017, p. 683.

53 Nair, ‘Archiving Womanifesto, and Much More….’, p. 16.

54 ibid.

55 Karen Steele, 'Gender and the Postcolonial Archive', CR: The New Centennial Review, vol. 10, no. 1, 2010, pp. 55–61.

Related pages

Share a Reflection

log in to share a reflection.