By Keiko Sei

Please note that this publication is currently under review and will be subject to changes.

When you enter the exhibition venue of 'Womanifesto: Flowing Connections' on the 8th Floor of BACC, the first piece you most likely will see is a grid-like installation that is made with fabric with hand-written text on the brick-like components, hanging from the ceiling. Despite its soft and airy feature, the piece holds the title, Building Up a Brick Wall.

This piece by Phaptawan Suwannakudt brought up a memory of my time in Europe where I often had to speak on a panel with Central European male philosophers. Often with the middle name of 'von' and fluffy hair in reality or in my imagination, because of their seemingly inaccessible profiles, and they would always present their theories that would begin by explaining Greek words. I regarded those vons as brick-builders as their job was to build theories based often on their interpretation of Greek. And they had to make sure that their theory brick walls were sky-high and solid, unbreakable and impossible to climb over. As a result, their brick walls would block communication and exchanges, and they would not relate to reality, as in their realm it was reality that had to adapt to their theories – and this was after the post-modern school of philosophy was supposed to have addressed the problem. Growing up in a different culture (non-logos based that is), language, as well as gender, I had to fight an uphill battle to establish my own mode of communication while not losing my own identity.

Then, one day, I had a chance to attend a completely different symposium from the ones that I usually had to attend. It was the year 2000, the place was Stockholm and it took place in conjunction with the exhibition entitled 'Text & Subtext: Contemporary Art and Asian Woman.' As the title suggests, the speakers of the symposium were all women from Asia, mostly from Southeast Asia. I remember having been so mesmerised by colorful and soft textiles that the speakers were wearing - coming from Central and Eastern Europe where most of the people only wear black or dark colors (I was wearing a black leather jacket when I met these Asian women), the site looked so fresh and new. Even when I grew up in Japan, the era was dominated by the Comme des Garçons-Rei Kawakubo-Yohji Yamamoto aesthetic, which means that I had not been familiar with tropical high-resolution pigments. I started to wonder if these soft and colorful textiles could be functioning as some sort of vehicle for communication down in Southeast Asia. The curiosity had grown enough to become one of the factors for me to subsequently move to the region.

These memories have vividly returned thanks to Suwannakudt’s installation. And, with these memories, the installation looked to me like an ironic take on the sturdy brick walls that these male philosophers and theoreticians have built up in the Western world (to note: the text that was handwritten on the fabric is taken from a history book, in an apparent attempt to deconstruct the grand-narrative of history written by male historians from dominant culture). It suggests in a quiet way that for women like us, words and texts are to touch and feel, to pass on, to communicate, and to sing and swing as wind blows away the grand narrative. A similar implication could be found in the baskets of Baskets of Experience by Karla Sachse, which are made from old local newspapers and hand-written texts and are made into shapes that defy the authorised use and function of the object.

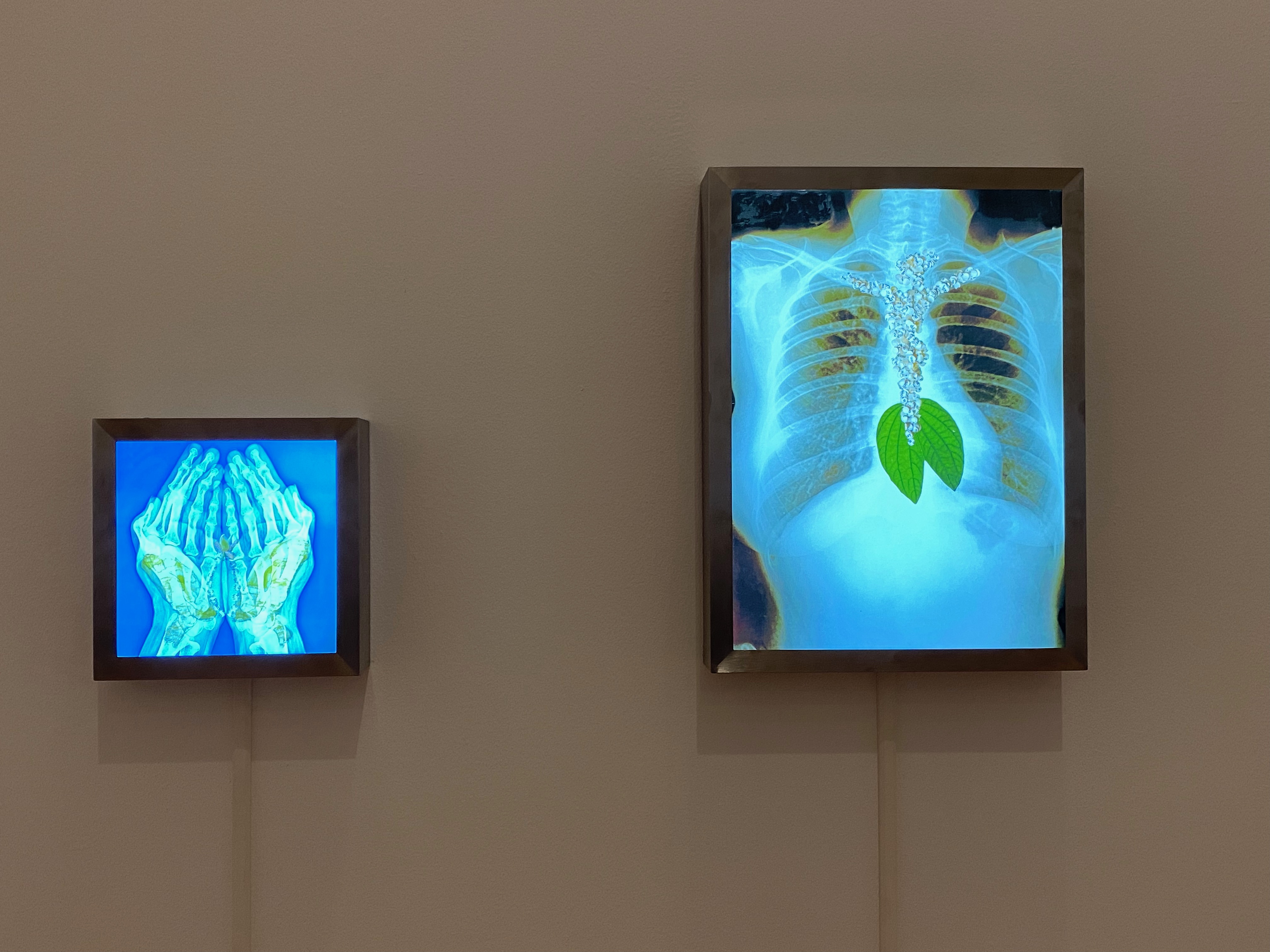

The challenge to dominant narratives has also been practiced in a series of works of Varsha Nair, the latest of which, entitled Moment of Truth, is exhibited at 'Womanifesto: Flowing Connections'. Started by a performance and video of her punching out letters from an ancient Indian text, the series has developed into various forms of manifestations including animation. Moment of Truth is a collage of X-ray photographs of various parts of a woman’s body and the punched-out letters as various movements. One of the prominent features of her works is that texts are always in motion and never sit still. The reason can be interpreted in various ways and the effect is equally various, but we can find the correspondence of the sentiment in the following poem by Jittima Pholsawek, one of the participants of Womanifesto.

[…] How can I dance/when soldiers with weapons are circling around and steel cages are open wide waiting/ How can I dance/when my fingers are taken off and the melody is tuned to the black hole./How can I dance… (Let me dance, Jittima Pholsawek)

This somewhat complex relationship between women and text, definitely more complex than that between men and text, is summarised in the name of Womanifesto itself.

Traditionally, manifestos have been written by men, especially young and ambitious ones, and the few written by women are from the West. They are usually dogmatic, imposing the writer's own belief in a self-congratulatory manner and excluding those who would not believe and follow the idea.

The manifesto of 'Womanifesto' is incorporated into the woman's body of text, which is a manifestation itself of the fact that women's manifestos are incorporated into their bodies in various forms, states and movements and thus are much more flexible and collaborative than traditional manifestos.

And this aspect of Womanifesto was perfectly demonstrated in the opening performance by Jarunun Phantachat entitled Dream a Little Dream. It was a dance performance in which the artist needed collaboration with participants who would read texts that questioned norms in order for her to continue dancing with her two legs. When no one was reading, she had to pause standing frozen often on only one leg, and therefore she was more prone to falling down. In short, the determined artist could have stood and danced on her own but she would have been stronger when she was fed with texts and when she had collaborations.

Womanifesto artists have started collaborating in the late 1990s without any flashy manifesto or fanfare. It was initiated by women artists in Thailand, and its main community village is located in the Isaan region. That makes the project doubly and triply marginal. It has been operating totally outside of the international art market — they have been doing things that were called for from within. In the installation Artist Hands by Lawan Jirasuradej, we see only hands of artists and artisans at work. For Jirasuradej, these no-nonsense working hands must have been the overall impression of the spirit of Womanifesto.

Looking at these compelling hands, the quiet battle that Womanifesto artists have fought for decades as triply marginal without any outside capital, which is tangibly ever more relevant in this age of attribute-driven identity politics, to archive, analyse and introduce. 'Womanifesto: Flowing Connections' is one of the fresh attempts to highlight the relevance.

As it happened at the site of the exhibition, I was given a culture for Kefir from a participating artist. The seemingly mundane act actually involved community effort: a person who had a culture handed it over to another person, who will cultivate it at home with care, and the cared-for culture will create a balanced living environment so that it makes even more people healthy. What could be more metaphorical than this in explaining what Womanifesto is all about, I thought, watching over the site of WeMend workshop where anyone can participate to create a collective colorful patchwork without being dictated to by any authority. The crucial network for this work was there — as, I would say, 'We have met'.

Related pages

Share a Reflection

log in to share a reflection.