By Phaptawan Suwannakudt

Please note that this publication is currently under review and will be subject to changes.

This text was first published in Womanifesto: Flowing Connections, Nitaya Ueareeworakul et al. (eds), exhibition catalogue, Bangkok Art and Culture Centre, Bangkok, 2023, pp. 42–47.

‘Do you believe in fate?’ The driving instructor said while placing a small shiny pebble into my palm.

‘If you like, you can make a wish and you may pass the driving test today.’

I had already got a Thai driver license, but I still required a test to get a registered license with the State of New South Wales. I took a driving lesson to get myself familiar with the new landscape and road conditions and asked the teacher to guide me around the nuances of body language, the nudges and gestures of other drivers who were sharing the road. I had only arrived in Australia three months earlier.

‘What are those for?’ The teacher noticed the Velcro straps I wore on both of my wrists while I was steering the wheel.

‘They are anti-nausea bands. They help reduce morning sickness during my first trimester...’

‘Whatever you do, don’t do it in this car.’ She said and we both laughed.

‘My mother can’t drive; my father doesn’t want her to learn.’ She said solemnly. We both stopped our laughter.

‘I can’t even teach her’. She continued.

No wonder why she decided to become a driving instructor.

I finally passed the test, not because of the pebble for which I did not make any wishes, but maybe because of my own will. I did it for my driving instructor, for her mother, for the child I was expecting who turned out to be a girl. And most of all, for myself.

Each culture has its own patterns and conditions for ones to negotiate their ways in which society they belong. I was one of the new arrivals to Australia, yet to cope with the way I would fit in. What I did not expect was that my driving teacher, a young blond with lively blue eyes, would have a father who stopped his wife, her mother, from learning how to drive. It was twenty years ago; we were about to enter the twentieth century when I had this encounter.

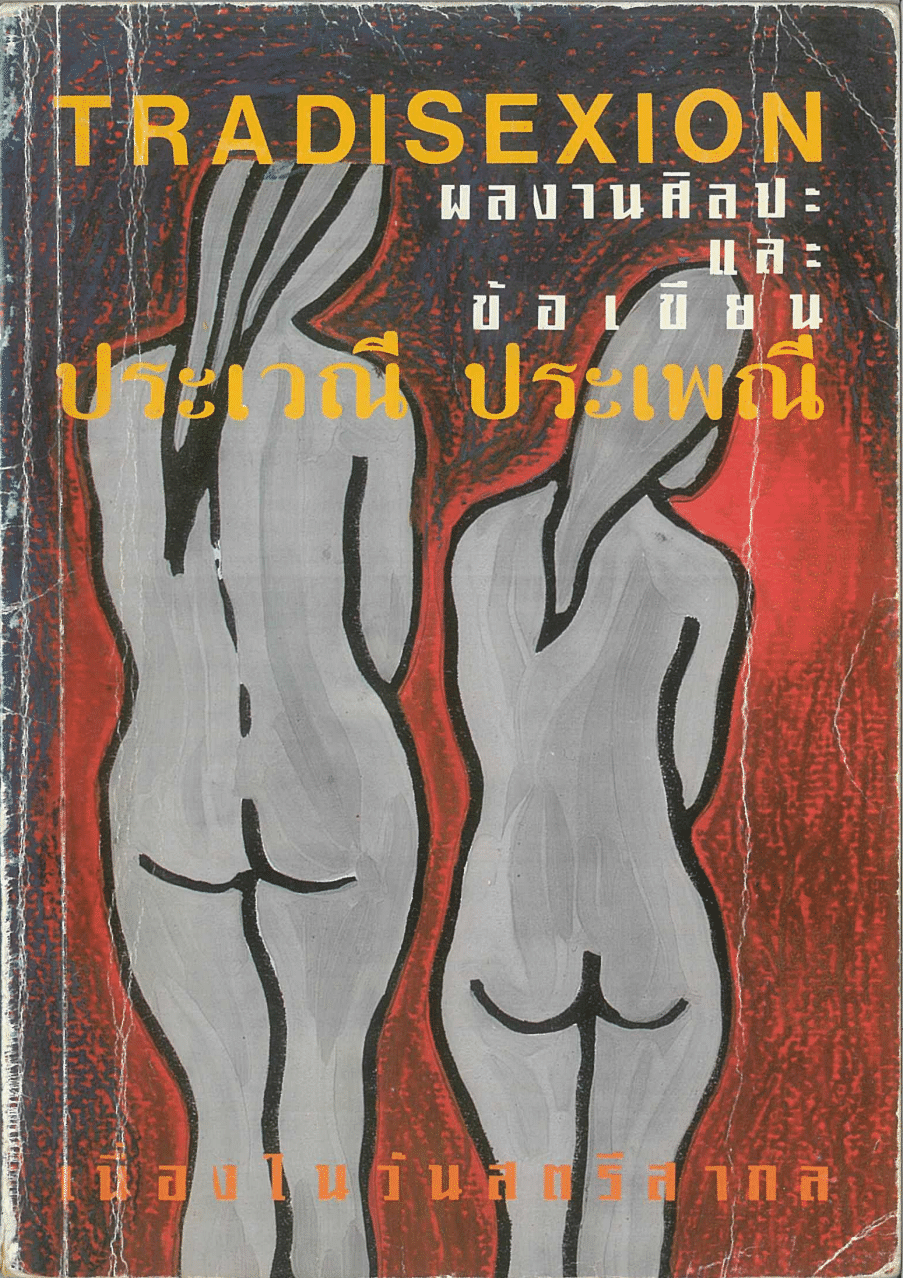

A year earlier, in 1995, I was in the group exhibition ‘Tradisexion’ at Concrete House in Thailand. I presented my work, Akojorn, which involved pieces of sarong hanging on a clothesline, a tabooed item for men in Thai society who could not go underneath because they would lose their power. It was the first time I produced work outside the context of Buddhist mural painting, which had been my career for the previous fifteen years. After ‘Tradisexion’, Mink Nopparat, whom I met briefly at my exhibition in Paris in 1989; Nitaya Ueareeworakul, who I was introduced by a common friend at the Alliance Française Thailand in 1990, and I, decided to go on to make another exhibition. We often hung out either at Studio Xang or at Nopparat’s home before we found the name ‘Womanifesto’ for the mission. After a couple of failed attempts to find a venue and support, we approached Rachada Thanaporn to act as the role of advisor. By halfway through, we still had not achieved any further development. I left for Australia with little to say to friends and family but simply—to make a new family. There was indeed more at stake than simple logic. It meant a lot to me personally to make such a move while I was at the peak in my career as a temple mural painter. There had been complex issues with personal dilemmas which resulted in my final decision—I realised that I had to leave. After fifteen years, I had more questions than answers to the artistic practice and narratives I did not see my voice within. I left with a heavy weight on my shoulders that I had not actually achieved what I promised with Nitaya and Nopparat.

I was more than grateful for Nitaya and Varsha to pick up the project and carry on building the network while overcoming the hardships of life with families in tow, let alone making art as a career for themselves. These were evident during the exhibition, ‘Womanifesto: Flowing Connections’, which has brought us back together. Nitaya, with her care and nurture and non-judgemental attitude, has always embraced and coped with what she had to deal with and this attitude shone. Meanwhile Varsha was being intricate with the work in terms of organising, which demonstrated care and labour of love during each project since the first iteration of Womanifesto. They are always my heroes; they are my hope and my refuge throughout time.

1996 was the year I set zero for my contemporary art career, without proper references and art academic degree, or any art prizes, or an inclusion in any international circuits. I found an easel set up by John, my future husband, on the first day I arrived. I had never taken his encouragement and ongoing support forgranted. Nariphon series took shape within days after I arrived. The narrative related to an incident took place near the first temple’s mural site in Payao province, where I worked. I was also inspired by the ideas and conversations I had with Noi Chantawipa, and the EMPOWER Foundation which she advocated for during the exhibition, ‘Tradisexion’. I sent the work to participate in the first Womanifesto exhibition in 1997.

Womanifesto did not simply emerge from nowhere or without reason. It was the action that quenched the thirst for a poorly supported space for women’s art practice which had no place to show itself. Womanifesto made women artists free to be just women, to have a voice from the ground up and not necessarily fit into the structure of the male-dominated art world. It was a puzzlement made visible by looking backward. Womanifesto is not a finished mould, but the cast made from time in spaces and circumstances around women’s places. Womanifesto did not have a flagship to arrive somewhere or to achieve anything in which we did not see ourselves fit. Women who gathered around through every single stage of their life, listened and shared issues with the support among friends and with a network which sustained itself. The network did not own the artists but allowed women to travel into, circumnavigate around, investigate the form, and add more to it. I recently replied when prompted to define what Womanifesto was with the three words: nature, feelings, and non-discrimination. The question was not about how Womanifesto began, but its longevity may tell how necessary this network had been to women and in particular for an outsider like me.

I grew up in a Buddhist temple and was brought up by my father who was against the art academy, which solely dominated the art scene in those days. The gap in the mural painting practice I learnt from him had never been more distant in any context from the value of the art. I spent time learning and painting murals for Buddhist temples with the narratives representing the Buddha and the stories which glorified his charisma. There had never been a place for a woman in the Sangha community in Thailand. I had become a mural painter, a rare place for a woman. I might be indeed the first woman who had led a group to execute a mural of my own design, but even so, I would never find the story of which I see myself within. A few opportunities where I would be included in group exhibitions were always annual charity sales of works donated to women’s shelter houses and the foundations for women. During the first year when I arrived in Australia, there was the gallery aGOG (australian Girl’s Own Gallery) run by Helen Maxwell, who told me the gallery was set up because there had been only 10% of women artists represented in prestige galleries in Australia then.1 When we created the world with ourselves at the centre, it already pushed someone who was not like us to the other side. Do we only have the binary of the opposites, men/women; black/white; East/West; high/low or national/foreign to look for the whole? Some exhibitions I was included in during my early years in Australia had titles regarding states of liminality, such as ‘Edge of Elsewhere’, ‘Second Language’, ‘Heading North’, ‘Threshold’, and ‘Crossing Boundaries’. I constantly felt adrift, never to have arrived and never to have quite departed. A structured place may also create a vacuum where someone fell and was left behind. The answer relied on who answered and to whose questions it addressed. Had we overlooked the social issues where the context of binary categories affected the livelihood of people? Most recently, I was included in a prestigious exhibition, ‘The National 2021’, a tag which I felt uncomfortable in defining myself.

In Australia, it was only as recent as 1971 that the Census of Population and Housing included the First Nation people as a population count for the first time, considering the 44 sheep were the number in the record of livestock which were brought in with the First Fleet according to Australian written history. This may indicate how Australians recognise and prioritise the existence of things based on our conveniences. There was a time when women, of all the citizens, were not allowed to cast their votes, uninvolved in the decision making for their own livelihood. At the time of this writing, Australians cast their votes in the referendum for ‘the Voice’ when previous attempts to acknowledge and deal with national issues for people of the First Nation had failed time and again. I was deeply saddened by the result that this year the proposed law did not pass the majority vote either.

When it came to figures and numbers, the Countess reported in 2014 that of the total pool of all artists in Australia, 70% were women. But when looking more closely at the art money pool in art prizes and museum collections, male artists dominated. Most of the Directors of the State Museums at the time of the count were male. At the launch of the website, Elvis Richarson, who had deliberately changed her first name to counter the count itself, admitted to the audience that it was a challenge to identify gender to names outside western culture—when it came to count at international venues such as Triennials and Biennales. My name is gender-less. In that sense, I sometimes get spams sent from dating site advertisements targeting male clients. Elvis admitted that she could only do so much when I briefly mentioned this to her at the exhibition ‘Know my Names’ at the National Art Gallery of Australia, which was based on the Countess’ finding. The exhibition claimed to include work of women artists throughout history to the present day across Australia, a gender equity initiative. I had been in Australia for twenty-six years, exhibited in four Biennales, and worked full time as an artist from day one to this—and apparently had missed the spot in the canon of Australian women’s art.

I came from the time and place where more than half of the girls in my class discontinued their study at primary school, the compulsory education at the time. More female than male school-leavers continued to grow by the time of the entry examination for university admission. A female university student in provincial Thailand once asked if she would make a career in art when she graduated, to which I struggled for an answer. I had an instant answer from a couple well-established female artists who insisted upon making ‘good’ art. The notion of ‘goodness’ may not take anyone anywhere based on my experience, particularly if they are, firstly, female, secondly, from a less privileged background with no network, and thirdly, having no committed support from family. My answer to the student was, change your mind if you do not think art is a necessity you cannot go without. However, if you think ‘art’ is necessary and ‘imagination’ is your priority, then ‘hope’ is an obligation, a duty which needs to be maintained constantly.

There has never been a question for me whether art would still be my choice if it does not make a career. I do not think I would live a life without making art for the only reason that imagination allows freedom. There is no gender race or religion, no rule, no structure, no dominance, and no instruction. I settle outside my studio and would be anxious to get back to the developing process of work when I could. I go to sleep with images in my head and wake up with ideas which inspire my aesthetic sensitivity and emotional intellect. This is precisely how art makes one feel human. However, the reality has been that even when I work twice as hard, and deliver twice as much, I still earn very little in comparison to other occupations in terms of revenue and prestige, let alone when compared to male colleagues. It is true that I have arrived at a place where rewards and recognition are there, and the conditions in the art have been improved from when I started the career. Nevertheless, I do not have to be on the less-full side to feel under privileged. There have been structural rules and standards which impose upon the art industries where I do not see that I can easily bend to fit myself in. My background practice does not necessarily fit in thematic categories which confuse curators, whose works are based on theoretical analysis. Precisely, my work is not collectable and commercially in trend.

I was one of the rare cases of female leaders who led a group of men and women to complete a temple mural project, with my sister following in my footsteps, but that did not happen out of nowhere. My late father was a feminist. He advocated for changes and justice. An artist before becoming an artist, he was brought up by a single mother, a silk weaver and a storyteller in one, a poet uncle and another philosopher uncle. His father, my grandfather, died when he was thirty-eight. His mother was a single mother who already had two children with former husband and looked after another four children who were born from my grandfather. He never judged women and only empathised with them for their conditions. Nevertheless, he could not convince my mother away from the idea that women needed to be protected by men.

I do not have to belong before-time or be precocious to understand inequality. I spent my life before ten within the periphery of the Buddhist temple in which my father led his painting team. To share my mother’s hard work, my father raised my two brothers and me while he was working to make sure that his children would have enough to eat. I was treated as inferior to my little brothers due to the fact that I was a girl. While my brothers could go on the raised platform which was made for monks, I was not allowed, which made me feel lower and ignored. I could not touch objects or food given to me by monks. Actually, those objects were let go and almost thrown to my hands to avoid touching the objects at the same time the monks were still holding them. I also learnt that I could not be ordained as a monk but as a nun, with much less status and conditions. I felt myself being less human. I had pride as a woman and had confidence in my talent. I had achieved a multi square-meter of temple murals and conducted projects which surpassed my father’s work during his lifetime, yet the temples were not my place. I moved to Australia and continued to work based on the background practice of Thai mural painting, which was expressed with the voice of a woman, the way that had never been a place in the conventional domain of Thai practice.

‘Womanifesto: Flowing Connections’ was held at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre twenty-six years after its first exhibition. The exhibitions and the presentation demonstrated how Womanifesto originated. It had been instructed during Womanifesto projects and events that participants did not have to work and had no other conditions. This would be easy to follow but did not make sense for many women, who were invited for the first time to participate during each project. The notion, ‘Not working’ and ‘let ourselves being’ may have stated loudly the way we resisted the power of dominance. The following is what Mae Pan, whom I met in 2008, related to the land, our meeting place during the Womanifesto residency at Rai Boon Bandarn in Sisaket:

‘This land [Boon Bandarn Farm], I feel, is ancient, and it is fated that I am here. We are all here too because it is meant to be. It is because of the land—we are related to the land. This land can educate people. It is a place where people come from everywhere to get something. In my lifetime, I thought of the land as becoming just this—for people to come and meet and feel joy.’2

For future generations, I asked friends’ children: Tara Ng (5), daughter of Yvonne Low; Isabelle Krischer (5), daughter of Shuxia Chen; and Suro Tunggal (7) and Trimo Asmara (4), children of Siobhan Campbell, to write the trilogy book of The Three Lady Ducks for ‘The Camel Library Project’ initiated by Nilofar Akmut. She was a long-time participant in Womanifesto who called out for artists in her network to write children’s books, originally aiming for a school in Pakistan which was since burnt down. It touched my heart to see the children, considered the youngest participants in the Womanifesto project so far, who would one day recognise that the books they had created were made for girls in the other part of the world where books were scarce and sometimes not allowed. That would be the day when the pebble performed the magic just by being itself.

1 The gallery has since changed the name to Helen Maxwell Gallery, where the number of female artists in galleries has risen to the equal of their male counterparts.

2 Pan Parahom, (Khun Mae Pan, 1939–2014) lived on Boon Bandarn Farm where she experimented with vegetation to make natural dyes for yarn, which she then wove into cloth. She welcomed Womanifesto for the workshop in 2001 and was a participating artist for Womanifesto Residency in 2008.

Related pages

Share a Reflection

log in to share a reflection.